It’s been 100 years since the Migratory Bird Treaty Act was passed and in that time, many bird species across the U.S. have declined. There are likely many causes for these declines, but one thing is certain: without monitoring populations, we wouldn’t know if species were increasing, decreasing, or staying the same. Monitoring an area as vast as the United States can be a challenge, but it is vital for bird conservation. Within the U.S., two large-scale monitoring programs collect data on bird populations every summer: Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR) and Breeding Bird Survey (BBS).

It’s been 100 years since the Migratory Bird Treaty Act was passed and in that time, many bird species across the U.S. have declined. There are likely many causes for these declines, but one thing is certain: without monitoring populations, we wouldn’t know if species were increasing, decreasing, or staying the same. Monitoring an area as vast as the United States can be a challenge, but it is vital for bird conservation. Within the U.S., two large-scale monitoring programs collect data on bird populations every summer: Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR) and Breeding Bird Survey (BBS).

Both of these programs aim to provide long-term datasets about bird populations that can be used to inform conservation decisions. Despite the similarity in goals and the use of point counts to collect information, the two programs differ in their methods.

I came to the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies as part of a summer capstone project to complete my Master’s degree at the University of Wisconsin. This capstone project places MS students with a conservation organization to apply the skills we learned during our coursework. This summer, I am working on creating various outreach materials about IMBCR. When I was first asked to write a guest blog, I did not understand the differences between IMBCR and BBS, but after reading papers, talking with experts, and going out on survey routes for myself, I now have a better understanding.

Common Nighthawks are one of many species experiencing declines.

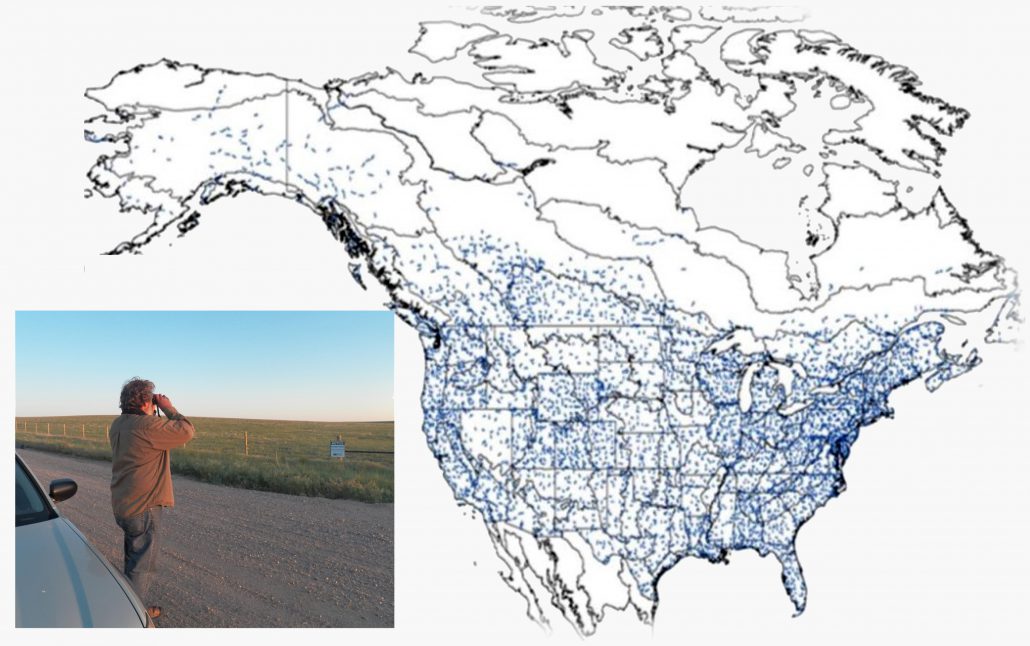

BBS was started in 1966. By 1968, it had spread across the entire continental U.S. and southern Canada, and recent efforts have been made to expand into Mexico. Each year, experienced volunteers drive approximately 3,000 routes to conduct bird surveys. A BBS route consists of a 25-mile long drive along a secondary road. Every half mile, the volunteer stops and conducts a 3-minute point count survey, for a total of 50 points along each route. During these counts, the species and number of individuals observed through both sight and sound are recorded along with wind, temperature, and cloud cover data. Due to limited road access, not all habitat types may be surveyed equally. This citizen-science project engages a large network of experienced volunteers. I enjoyed the opportunity to join Arvind Panjabi, Bird Conservancy’s Director of International Programs and a BBS volunteer, on his route through the Pawnee National Grasslands. Arvind shared his birding expertise, teaching me how to identify many species new to me—by sight and song— such as the McCown’s Longspur.

Bird Conservancy’s Arvind Panjabi is also a BBS volunteer. Here he is conducting a roadside survey near Pawnee National Grasslands. The map at right depicts the paths for existing BBS routes across the U.S. and Canada. The BBS has recently expanded into northern Mexico (routes not shown) and there are plans to expand the survey into central Mexico and points further south. Figure © Breeding Bird Survey.

BBS data are used to estimate long-term population trends and understand geographic patterns of population abundance. This allows for analysis of the relative importance of an area to a species and landscape-scale habitat associations. These data are also used by Partners in Flight, a network of organizations committed to landbird conservation, to get a rough estimate of regional population sizes. With its large geographic coverage, analysis of populations can be conducted at scales from the full range of a species down to individual states or Bird Conservation Regions (BCR). Currently, trend analysis for about 400 species is available, and as more data have accumulated on less common species, analysis on another 100 species may soon be available.

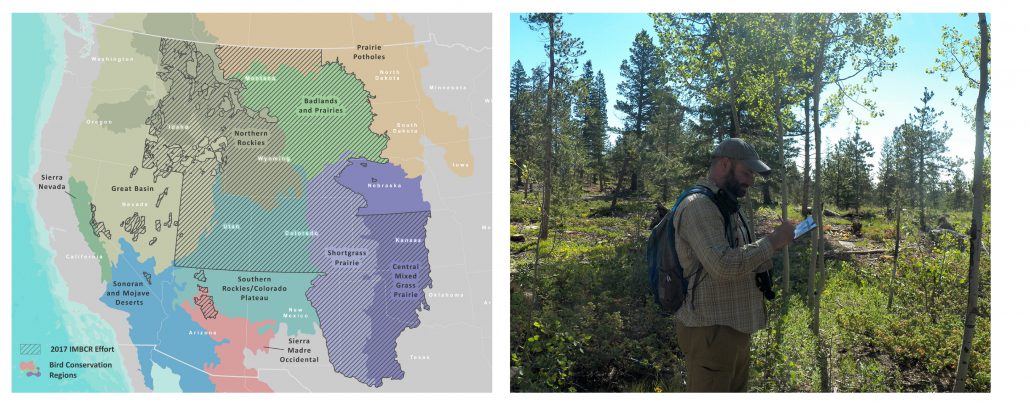

IMBCR began in 2008, so it does not yet have the same time extent as BBS. It currently covers three entire states and parts of 12 states and continues to expand. Each route consists of a 1 km square grid with 16 point count locations. Paid observers hike to each point and conduct 6-minute point count surveys, recording the species of each bird seen and heard, as well as the distance of each bird from the observer, its sex, and whether it was identified by sight or sound. Like BBS, wind, sky, and temperature conditions are recorded as well as details about vegetation such as average tree height and cover. This program uses a spatially balanced random sampling design and every habitat type is included, from remote mountaintops to busy urban areas. Many IMBCR routes require off-trail hiking, which I got firsthand experience with while participating in a survey in the Colorado mountains. Whether it is finding an unmarked road at four in the morning or trying (and in my case failing) to avoid tripping over downed logs, off-trail routes provide an extra challenge!

Map of Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions coverage and an IMBCR biologist recording vegetation data on a survey.

While IMBCR does not have the same geographic extent as BBS, their methods allow for robust population size estimates for over 250 species. With this design, population sizes can be estimated at scales from whole states or BCRs down to individual management areas like a single national forest. The collection of vegetation data also allow for detailed analysis of small-scale habitat relationships. This kind of information can be used to connect the effects of landscape changes or management action to changes in bird populations. Through these methods, IMBCR can engage in question-driven monitoring and link this to adaptive management.

These two monitoring programs were designed to provide specific kinds of information, and they fulfill their purposes well. Whether one or the other program is used depends on the objectives of those using the data and the resources available. For avian conservation as a whole, these two programs can provide complementary and valuable information. When it comes down to it, no program is perfect. But, I think Keith Pardieck, the National Program Coordinator for BBS, put it best: “It is a red herring to criticize a program for what it wasn’t designed to do.”

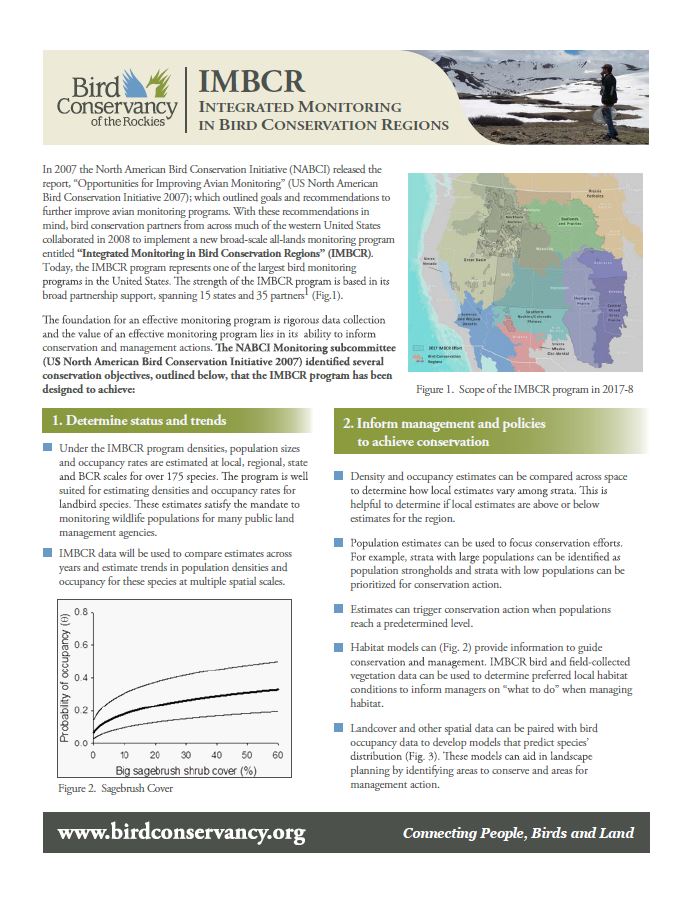

The IMBCR program is delivered through a broad partnership and with the support of dozens of other organizations. Click the image at right to download a detailed factsheet.

The IMBCR program is delivered through a broad partnership and with the support of dozens of other organizations. Click the image at right to download a detailed factsheet.

The Rocky Mountain Avian Data Center serves as the portal for avian information collected by Bird Conservancy of the Rockies and our collaborators in the Rocky Mountains, Great Plains and Intermountain West. The Rocky Mountain Avian Data Center also acts as a regional node of the Avian Knowledge Network (AKN). The data center is a source for current data, results, methods and materials produced. This information is available to the public, researchers, land managers and partners.