Less trees, more forest

Trees define forests, but more trees do not necessarily make better forests. In particular, lower elevation conifer forests in western North America typically have low densities of large trees interspersed by open, park-like conditions. Frequent low-severity wildfire—sometimes intentionally set through controlled burns—helps clear shrubs and smaller trees, keeping vegetation density low, and favors fire-resistant trees like ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa). Additionally, wildfires burn some areas more severely, leaving large forest openings and maintaining diversity across forest landscapes.

Prescribed fires like this one by the U.S. Forest Service in Colorado are a useful forest management method. Photo by Pew Charitable Trust.

Many wildlife species, including birds, have evolved in these relatively open forests, and heterogeneous forests can support a diverse assemblage of species adapted to various conditions. Over the last century, fire suppression has altered forest structure resulting in greater densities of smaller trees, denser understory vegetation, and more homogeneous forest landscapes. These changes along with warming temperatures have increased wildfire severity and extent, threatening the integrity of many forests and the habitat they provide for many forest wildlife.

Restoring forests by removing trees

The U.S. Forest Service’s Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP) aims to address human impacts on forests by promoting collaboration-based, landscape-scale forest management. Mechanical thinning and prescribed fire reduce canopy and understory density while encouraging large fire-resistant trees like ponderosa pine. Along with improved ecological integrity, forest managers expected restoration to improve habitat for wildlife species by restoring conditions with which they evolved. CFLRP mandates and funds monitoring to verify the effectiveness of forest restoration, but monitoring typically focuses on vegetation, leaving implications for wildlife unclear.

A diverse array of birds rely on healthy conifer forests. L-R: Mountain Chickadee, Red Crossbill, Pygmy Nuthatch (Ian Routley) and Williamson’s Sapsucker (Chris Wood)

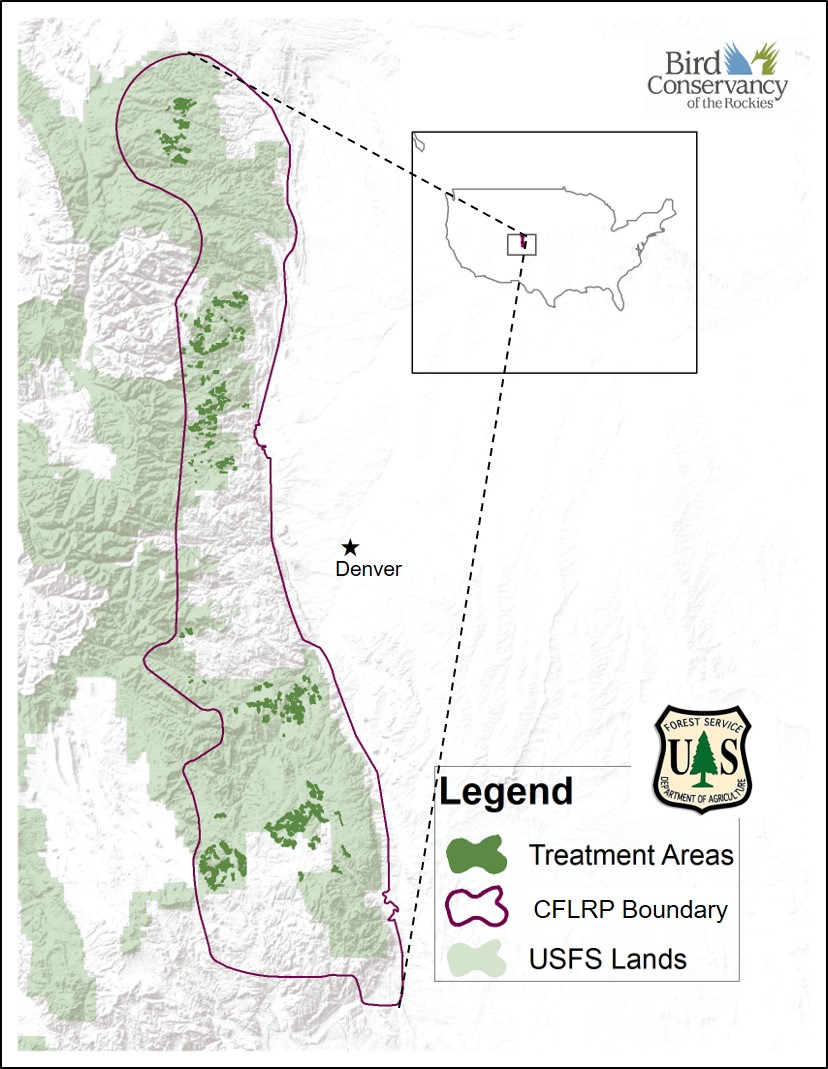

Monitoring bird responses on the Colorado Front Range

The Forest Service administers CFLRP efforts along the Colorado Front Range, for which multiple stakeholders collaboratively develop treatment prescriptions. Prescriptions include local ecological and economic objectives but share overarching objectives of creating historically relevant stand conditions, reducing canopy cover, creating persistent openings, and encouraging heterogeneity at multiple scales. The wildlife committee for the Colorado Front Range CFLRP identified birds as a focus for monitoring wildlife habitat objectives.

Click the map to view the CFLRP Program Projects and Activities Map Viewer.

Accordingly, they funded extension of Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservancy Regions (IMBCR; administered by Bird Conservancy of the Rockies) to examine avian relationships with treatments and vegetation attributes targeted by treatments. IMBCR surveys provide data on a wide range of bird species at two spatial scales, allowing us to examine species and community relationships with restoration treatments locally and at a landscape level. We anticipated that these forest management actions would benefit bird species associated with open ponderosa pine-dominated forests locally, while also increasing variety and thereby widening the range of species supported across the landscape. The monitoring and subsequent research aimed to confirm this assumption.

Win some, lose some (locally)

Looking at specific locations (150-m radius sites) where treatments had (or had not) been implemented, we found both positive and negative relationships with restoration treatments, reflecting differences in species lifestyles and habitat affinities. Some aerial insectivore species, such as Olive-sided Flycatcher and Western Wood-Pewee, were more prevalent in treated forests. Treatments may encourage more productive understory vegetation in canopy openings, supporting more flying insects and creating more opportunities for catching these insects on the wing.

Larger pine trees experience less competition in more open forests, allowing them to produce more cones and perhaps explaining apparent benefits for species that feed on ponderosa pine seeds, such as Clark’s Nutcracker and Pygmy Nuthatch. Species associated more with closed-canopy forests and some that nest or forage in shrubs were less prevalent at treated sites, potentially due to the reduction in canopy and shrub density with treatment. Overall, we found a similar number of species that were more prevalent versus less prevalent in treated versus untreated sites.

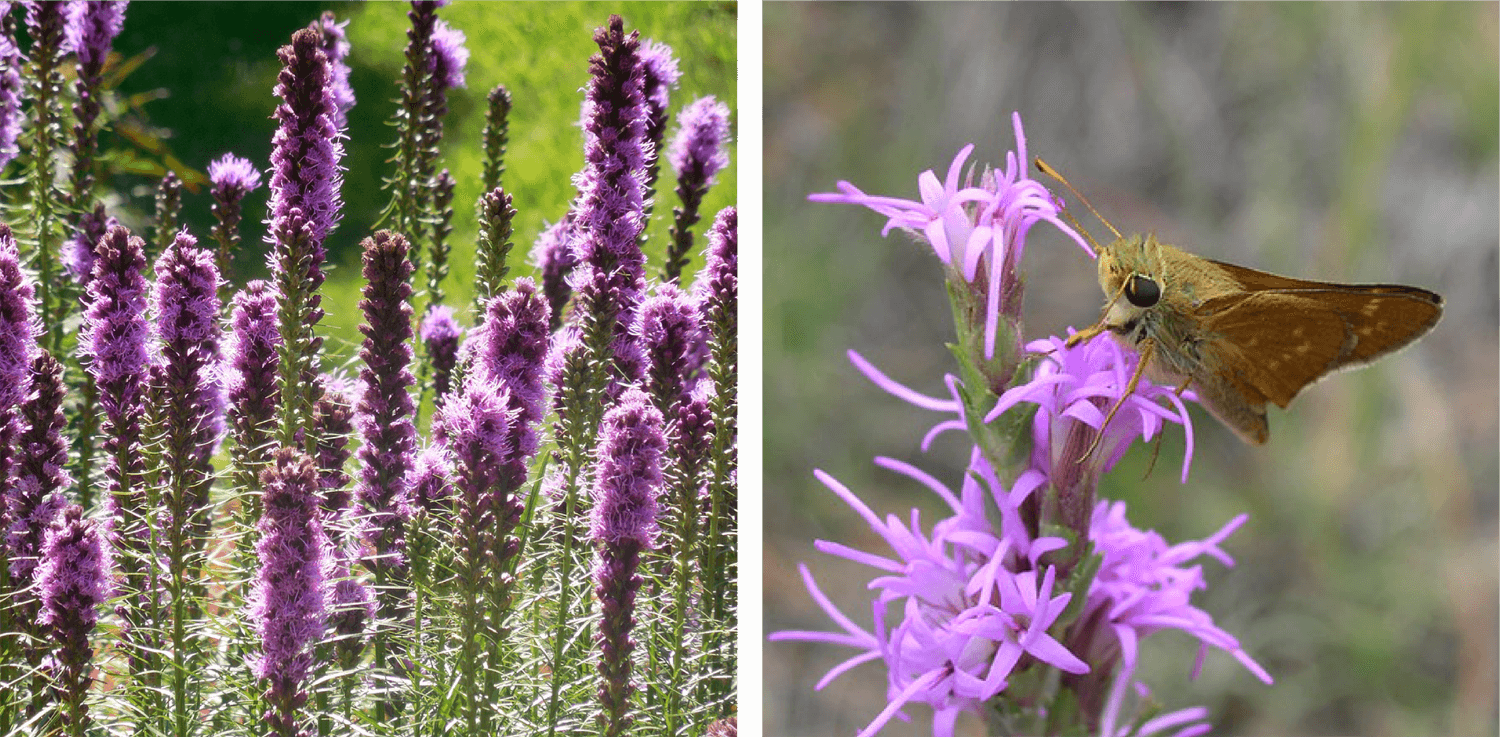

Forest treatments that open the canopy benefit more than birds. Prairie gayfeather, critical for the threatened Pawnee montane skipper butterfly, thrives in treated zones. Photo: Craig Hansen USFWS

Restoration benefits bird communities across landscapes

Although we found different relationships with treatment locally, we found consistently positive relationships with treated landscapes (1 km2 cells). Sixteen species exhibited statistically-supported positive relationships with the extent of the landscape treated, whereas none of the 103 species detected in our study exhibited negative relationships at this level. Consequently, species richness (the number of species present on the landscape) increased with increasing treatment extent. This pattern suggests CFLRP treatments can benefit avian communities by generating habitat for open-forest species without eliminating habitat for closed-forest species, allowing both to co-exist across the landscape.

Special thanks to the following for their collaboration and support:

USFS Rocky Mountain Region • Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests • Pike and San Isabel National Forests • Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program • Front Range Round Table • IMBCR partners • Colorado Forest Restoration Institute