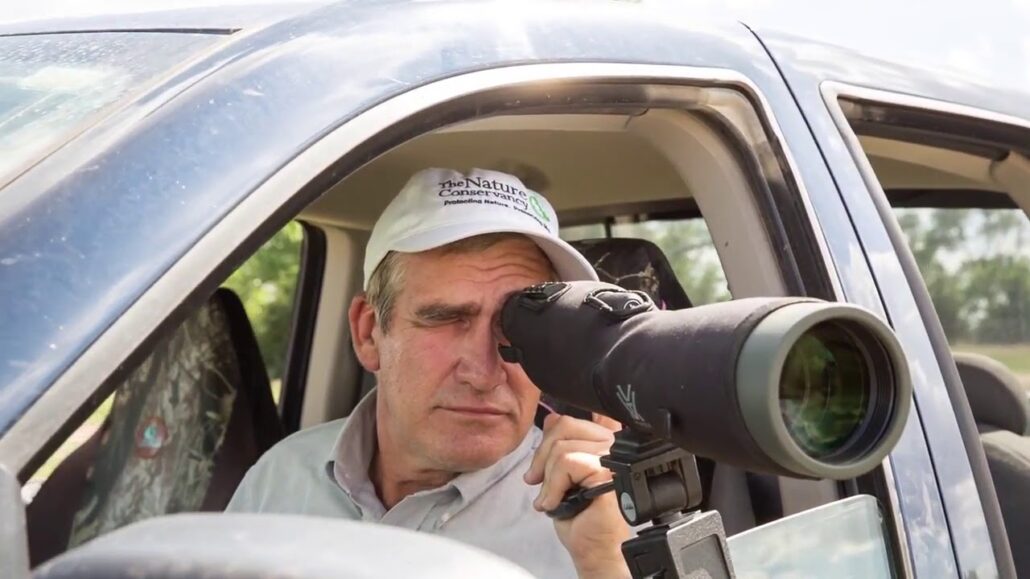

This is a guest post by Robert Penner, Avian Conservation Manager at The Nature Conservancy, and the 2021 recipient of Bird Conservancy’s Richard G. Levad Award.

Bird conservation requires partnerships between organizations and across borders and countries. I am fortunate to be able to work with a number of conservation organization across the Western Hemisphere and one of the best is Bird Conservancy of the Rockies. I will admit that many don’t associate shorebirds with the Rocky Mountain region, but Bird Conservancy’s work in the Great Plains is instrumental to the survival of many grassland-loving migratory shorebirds, such as the Mountain Plover, Long-billed Curlew and Upland Sandpiper, to name just a few.

Although I marvel at the distance in which some shorebirds migrate, not all shorebirds are long-distance migrants; the American Woodcock migrates only a short distance and avocets, stilts and dunlins migrate moderate distances, thus spending the winter mostly in the southern United States. Of the shorebirds species that breed in North America, a clear majority migrate to wintering grounds in the temperate and tropical regions of Central and South America, with most making a round trip of 7,500 miles, and some traveling 15,000 miles.

I find it interesting that some of those shorebirds that breed farthest north also winter farthest south. Shorebirds whose breeding and wintering grounds are far apart must replenish their fat reserves during migration. They need to accumulate fuel and will burn several times their body weight in order to complete the long journey. They do this by stopping at a chain of staging areas, such as the Texas Coast, Cheyenne Bottoms in Kansas, the Rainwater Basins in Nebraska, and the Prairie Potholes of the Dakotas. Often however, some shorebirds take long flights of 2,500 miles or more at a time. Before shorebirds begin migration, they undergo hormonal changes, inducing them to put on fat, and only after they have put on enough fat reserves do they begin migration. Those shorebirds that make migrations of 1,500 to 3,000 miles over inhospitable areas such as oceans, glaciers, deserts and even the Great Plains during dry years, first must double their body weight. These fat reserves will carry them nonstop for three or four days.

- Black-necked Stilt. Photo from Dover North American Birds.

- Dunlin. Photo from Dover North American Birds.

- American Woodcock. Photo by Fyn Kynd (CC by 2.0).

When it comes to shorebirds there are three major flyways or migration corridors that link breeding and wintering sites across the Western Hemisphere. Current views on the migration of shorebirds are derived primarily from studies of the coastal Atlantic and Pacific flyways. In coastal areas, several species of shorebirds stop at relatively few sites where food Is abundant and predictable. There are probably no alternative coastal sites that could provide enough food for these large aggregations of shorebirds at precisely the right times to ensure successful migration.

In contrast to coastal areas, where I live in the Midcontinental Flyway, particularly in the Great Plains, the dynamic patterns of rainfall and hydrology result in extreme distance and time variability in both occurrence and condition of wetlands. But it is not just wetlands that are important to shorebirds. A number of shorebirds depend on grasslands, and the loss or degradation of these grasslands can have dire effects on the future of these birds. Large permanent wetlands such as the Salt Plains in Oklahoma or Cheyenne Bottoms, where I am located, may provide the most predictable resources for interior migrants, but even they are less predictable than coastal areas.

- Wetland at Cheyenne Bottoms, KS.

- American Golden-Plovers at Flint Hills, KS.

Shorebirds as a group are extremely diverse in body size and shape as well as in habitat-use patterns and foraging behavior. Migrants in the Western Hemisphere range from 6” to 25 ½” in body length and from ½” to 8 ½” in bill length, and ½” to 3 ½” in tarsal length. Thus, habitat use is determined in part by characteristics. Collectively, shorebirds use a broad range of habitats, including grassy uplands, wet meadows, unvegetated mud flats, shallow water, and deeper open water. While feeding, shorebirds glean invertebrates from the surface of the mud or water, or from emergent vegetation or probe deeply into moist soil, or even catch flying insects.

- Robert and Masters student Gentry in the field.

- Masters student Kirsten preparing field research equipment.

Threats to shorebirds have become more diverse and widespread in recent decades and pose serious conservation challenges. Unregulated hunting, predators, human disturbance, habitat loss, habitat degradation and climate change threaten these birds’ survival. We can reverse these downward spirals across the flyway, but we must act fast and undertake our own collaborative, far-reaching call to action. Effective conservation requires a wide-ranging approach to identify and reduce threats throughout the flyway. To be truly effective, such an approach must coordinate research, conservation, and management efforts of many groups across multiple political boundaries and consolidate resources.

The organization which I work for, The Nature Conservancy, has made the commitment to protect places like Cheyenne Bottoms and the Flint Hills, in part because of their importance to shorebirds. However, if we do not work on shorebird conservation along the entire flyway, any efforts to manage these sites as a prime stopover or nesting sites for shorebirds will be a waste of time and energy. Shorebird conservation is not just a local issue, it truly is an international issue. One organization, nor even one country, can accomplish the conservation work that is needed to protect this group of birds.

In the video above, Rob provides a behind-the-scenes view as Bird Conservancy of the Rockies installs two Motus towers (sponsored by The Nature Conservancy) at Cheyenne Bottoms. These new towers are part of the Kansas Shorebird Radio Telemetry Project and will provide crucial data about shorebird and grassland bird movements throughout the Great Plains.

I am inspired by Bird Conservancy’s mission of the conservation of birds and their habitats through an integrated approach of science, education, and land stewardship. I look forward to more opportunities for The Nature Conservancy and Bird Conservancy of the Rockies to work together and do even more great conservation work in my beloved Kansas.

Robert Penner is an Avian Conservation Manager at The Nature Conservancy, and is the 2021 recipient of the Bird Conservancy’s Richard G. Levad Award. During the spring of 2022, Robert will be assisting his master’s degree student with her research on the effects of our various grazing treatments on avian use and nesting success. She is the twentieth graduate student for whom he has served on a graduate committee during his twenty-four years with The Nature Conservancy.

All photos were provided by Robert unless otherwise noted.