Mexican Spotted Owl Photo by Morgan Callahan

Meeting the owl

In a dark forest of the southwest, a male Mexican Spotted Owl flies silently through a thick stand of intermingled pines, oak and aspen. The owl veers from its course to reach the top of a Douglas fir, a woodrat dangling from its beak. Perching on a small branch, the owl waits for the quiet begging calls of its mate nearby. Its female sits snugly on two pale eggs atop a thick witch’s broom, an ideal nesting platform. After transferring the woodrat to its mate, the male finds a new perch from which to scan the forest floor in search of its next meal. Its attention is soon interrupted by a familiar yet unwelcomed sound: an intruding Spotted Owl calling in the night.

Down below, two wildlife technicians play a pre-recorded call of a Spotted Owl in hopes of eliciting a call-back response from the territorial male. Luck is on their side this evening, and both technicians gasp as an ascending hoot breaks up the repetitive calls coming from their speaker. The owl is perched about 200 ft away, but its boisterous calls can easily be heard in the otherwise still night. As one technician turns off the speaker, the other carefully triangulates the owl’s position using a handheld GPS and compass before recording it on a datasheet.

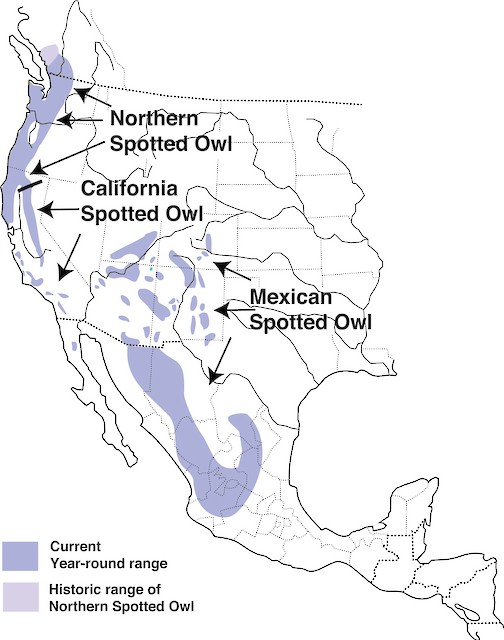

Since 2014, Bird Conservancy of the Rockies has been working hand in hand with the U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to monitor Mexican Spotted Owl populations (Strix occidentalis lucida). One of three subspecies of Spotted Owls, the Mexican Spotted Owl is smaller and lighter in color than its more northerly distributed counterparts. This medium-sized owl sports a mottled brown plumage speckled in white– perfect camouflage for blending in with bark. Mexican Spotted Owls have a broad distribution, spanning from southern Utah and Colorado to the Sierra Madre range in Mexico. While Spotted Owls are the emblem of the old-growth redwood and Douglas fir forests of the Pacific Northwest, the Mexican subspecies can be found anywhere from red sandstone canyonlands to deep gorges typical of the Guadalupe mountains. Their favored habitat consists of mixed conifer-oak forests with cooler microclimates created by local elevation and terrain. Northwest-facing slopes and drainages stay cooler than the surrounding area; these are the perfect refugia for an owl adorned with thick plumage. A mixed forest of firs, pines and oaks creates suitable habitat for their preferred prey, the wood rat. Finally, mature Douglas firs and White firs towering over the forest floor offer ample nesting opportunities. As these trees age, their center bark rots from the inside and eventually break near the top. Branches below the break grow and twist up to shade the exposed inner bark, providing a perfectly protected bowl-shaped place to lay eggs. When broken-top trees are limited, mistletoe infecting large conifers is a great alternative for nesting.

Map showing the distribution of the three subspecies of Spotted Owls, obtained from Birds of the World (www.birdsoftheworld.org).

Federal Protections

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, the logging industry was booming and taking full advantage of the huge swath of large conifers in the National Forests of the southwest. Many towns in Arizona and New Mexico, such as Flagstaff & Española, were born from the logging industry and thrived. While the lumber extracted from the region benefited development across the US, conservation organizations began to pay attention to the Timber Wars in the Pacific Northwest and the listing of the Northern Spotted Owl as a threatened species. Could the Northern Spotted Owl be a harbinger of population declines for the Mexican subspecies with subsequent regulatory implications? Unfortunately, little was known about these secretive birds which limited the guidance available for sustainable forest management.

In 1989, a petition to list the Mexican Spotted Owl under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) was submitted to the US Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS). This began a lengthy process of considering the threats, population trends, distribution and needs of the subspecies. A little more than 3 years later (in March of 1993), the FWS was ready to make a final decision. The agency concluded that the continuation of logging and the potential of large wildfires posed significant threats to the owl’s long-term persistence, and listed the Mexican Spotted Owl as threatened under the ESA. As a result, federal agencies are required by law to mitigate management impacts and assist recovery efforts by conserving owl habitat and tracking population trends on both federal and private lands. This decision had cascading consequences for many federal agencies which strive to balance multiple competing objectives, including multiple land uses and wildlife conservation.

A complex conservation issue

Despite its undeniable charm, the long-term persistence of the Mexican Spotted Owl in southwestern forests has been the subject of decades-long conflict. In Arizona and New Mexico, the majority of Spotted Owls occurs within the jurisdiction of one agency: the U.S. Forest Service (USFS). Since the listing of the subspecies, Wild Earth Guardians have filed multiple lawsuits against the agency claiming it failed to monitor Spotted Owl populations and habitat. Much like for the Northern Spotted Owl, an important issue at stake was timber management on federal lands and the resulting impacts to owl habitat. This placed the agency in a difficult position: balancing its sustainable multiple use mandate, including wildlife recovery efforts and management that supports the livelihood of many local communities. In 2020, the latest lawsuit was resolved and additional funds and capacity were devoted to monitor owl populations and habitat, but management and conservation challenges still remain.

Monitoring by Bird Conservancy of the Rockies

A vital component to understanding progress on the species’ conservation is to understand its population status- is it declining, stable or increasing? The USFS, therefore, needed a way to check the pulse of Spotted Owl numbers- a daunting task considering the agency’s limited resources. Beginning in 2014, Bird Conservancy partnered with the Southwestern Region of the USFS to assist with long-term monitoring of Mexican Spotted Owl populations and try and address some of the lawsuit’s key concerns. The study region was constrained to areas within National Forests potentially suitable for owl habitat based on vegetation, climate and topographic characteristics. Within this suitable habitat, we selected a spatially-balanced subset of randomly generated locations from which to monitor Spotted Owl populations.

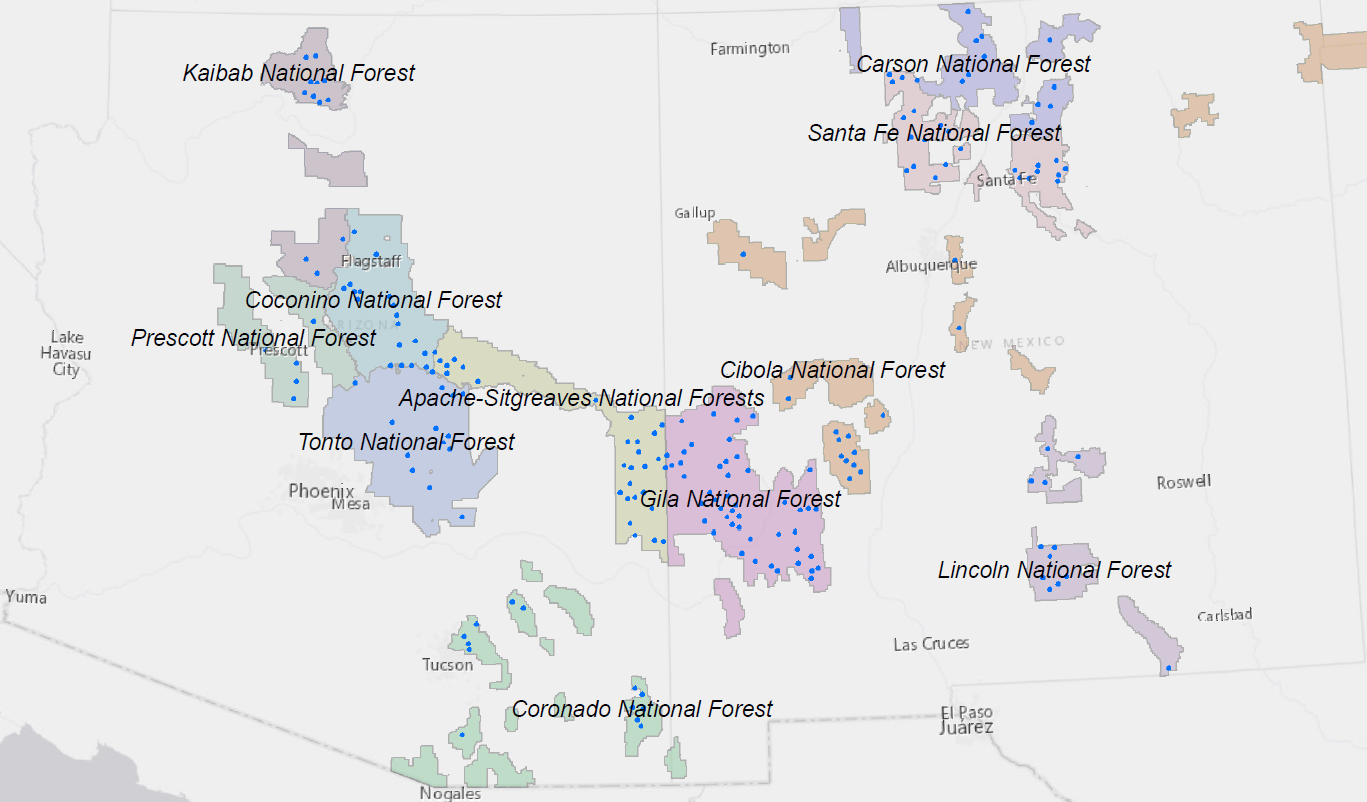

Sites surveyed for Mexican Spotted Owls (blue dots) span 11 National Forests, 44 Administrative Forest Districts, and 26 wilderness areas across Arizona and New Mexico.

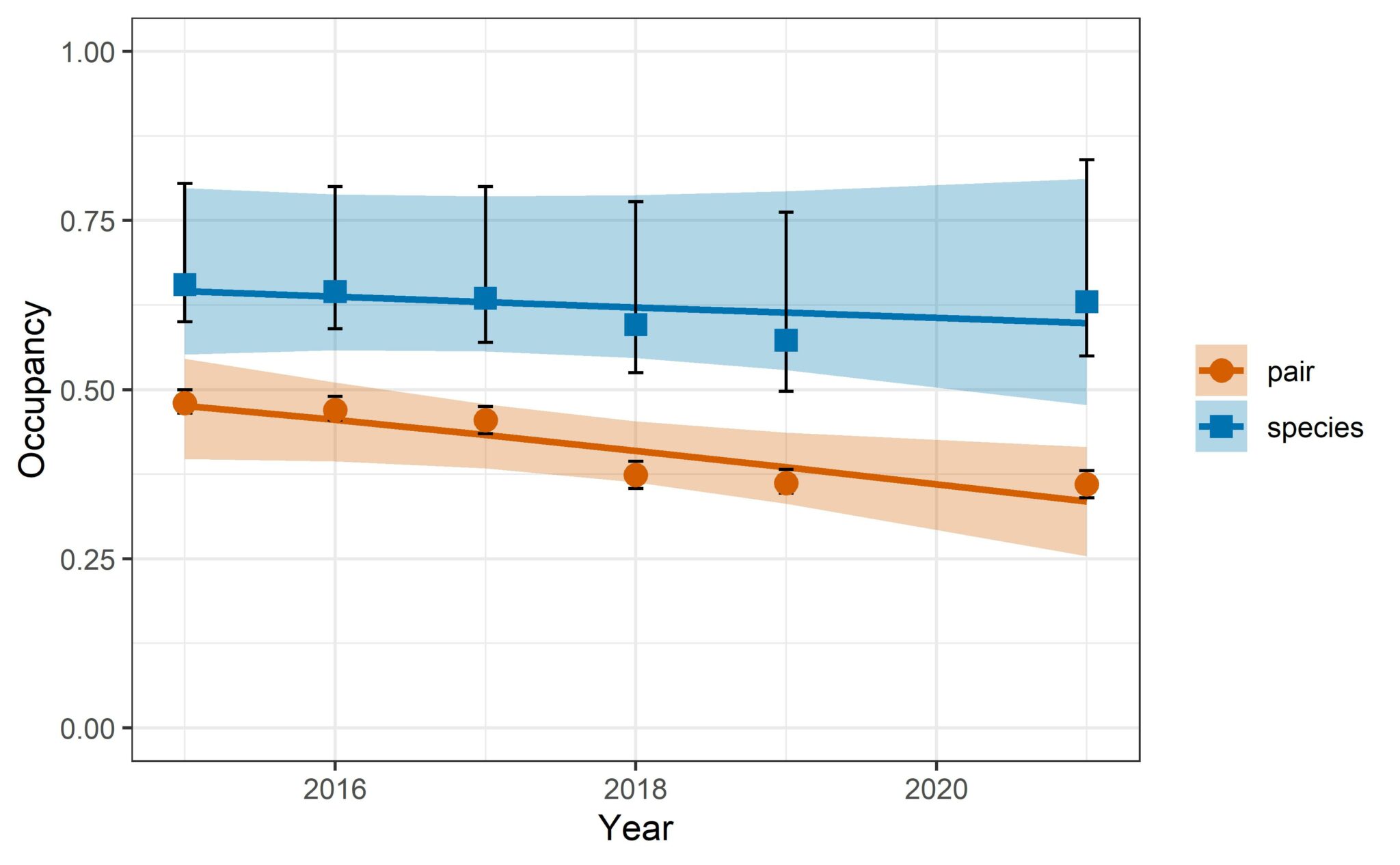

Since then, Bird Conservancy conducts annual surveys on approximately 200 sites distributed across Arizona and New Mexico. Detections of Spotted Owls are used by staff scientists to model annual occupancy for breeding pairs (male and female found one territory) and the species overall (individuals owls and pairs combined). Changes in occupancy are used to estimate population trends for both pairs and for the species throughout the region. Currently funded by USFS through 2025, this study is now in its 7th year and is currently the only long-term, large-scale monitoring effort for the Mexican Spotted Owl. Upon its completion, Bird Conservancy will deliver findings from a 10-year assessment of MSO population trends to the USFS and FWS, which will be used to inform the subspecies’ recovery goals and update federal listing status in the future. The owl’s latest federal recovery plan outlines specific goals that must be reached in order to delist the subspecies. The owl must have a stable or increasing population over the 10-year period, and studies reporting on population trends must have a 90% probability of detecting a 25% population decline or greater (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2012). Spotted Owl populations are presumed to fluctuate with prey availability and monsoons, which highlights the need for long-term monitoring to draw robust inference on population trend. Although preliminary analyses seem to indicate a slight decline in pair occupancy but a stable species trend, we are continuously working to improve the precision, and therefore, confidence in our estimates to match the recovery goals.

Preliminary results of Mexican Spotted Owl occupancy from 2015-2021. Occupancy was modeled using a hierarchical conditional occupancy model, where female-male pair detection is a condition of detecting the species (one or more owls). Results indicate a stable species trend but a slight decline in pair trend.

In the field

Bringing these data to life is far from a walk in the park. The owls favor steep drainages and dense mixed-pine forests at high elevations, which can make for treacherous work at night. Survey work begins a few hours before sundown, when technicians unfold paper forest maps and chart their path to the site. Technicians must arrive at a site with enough time to hike in (anywhere up to 6 miles) before sundown. Once at a site, crews use a loudspeaker to play owl calls and listen carefully for a response. Depending on the terrain, surveys can sometimes take up to 2 hours to complete. Nocturnal work increases the hazards associated with off-trail navigation, remoteness, weather and wildfires. In addition, encounters with mountain lions and bears are common and certainly memorable. For this reason, Bird Conservancy seeks to hire individuals with ample backcountry experience and provides a 5-day training before the field season. The field season is rarely without challenges, but the rewards are often greater than the sacrifice. As Adrienne Cunningham, a crew leader on the project, said: “Encountering Mexican Spotted Owls in their natural habitat is truly an honor…[Knowing] this project contributes to our knowledge of the species to protect it is a rewarding experience in many ways”.

- Technicians on the Mexican Spotted Owl project attend a 5-day training to refine their navigation and backcountry skills.

- Sites surveyed for owls require stable footing and good cardio, as they are often steep and adorned in spiky vegetation. This beautiful site is in the Guadalupe Mountains, Mexican Spotted Owls use the drainages for nesting habitat. Photo by Marion Clément.

Future work

Bird Conservancy is committed to continue this work and extend the applications of this dataset to serve the needs of our partners, such as USFS. Many of our collaborators contribute to the subspecies recovery and are leading innovative investigations to shed light on the needs of this elusive owl. Gavin Jones, Research Ecologist at Rocky Mountain Research Station and colleagues created a suitable habitat map called the “Living Map” that is being used to track historical and current habitat trends for the owl. Shaula Hedwall, Senior Fish & Wildlife Service Biologist, is leading field experiments to determine how managed forest fires and timber thinning can be implemented without disturbance to breeding owls. The threats to the species are continuously evolving, and currently large destructive wildfires and prolonged droughts are of key concern. We are extremely grateful to our USFS Region 3 partners, including Ron Maes, Becky Kirby and the many others who have contributed to the project over the years. Finally, a huge thanks is owed to Jennifer Blakesley and Wendy Lanier, who led the project for many years and made long lasting contributions.

Wildfires in the southwest are of increasing concern for the Mexican Spotted Owls, and are challenging to work around to survey our sites. Photo by Marion Clément.

Marion Clément is our Mexican Spotted Owl Coordinator and is based in our Fort Collins office.

Citations

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Final Recovery Plan for the Mexican Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis lucida), First Revision. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA. 413 pp.

I love your blog.. very nice colors & theme. Did you create this website yourself? Plz reply back as I’m looking to create my own blog and would like to know wheere u got this from. thanks