Birds can migrate thousands of miles a year between their breeding and wintering grounds. Where, exactly, do they go? What routes do they take and where do they stopover? In 2012, Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory biologists set out to answer these questions for Western Tanagers and Swainson’s Thrushes that breed in Rocky Mountain National Park in a project for the National Park Service.

“It’s important to learn about these local sub-populations,” said Jason Beason, Special Monitoring Projects Coordinator for RMBO. “If they have different wintering grounds, we need to know where they are in order to monitor for population declines and focus our conservation efforts.”

Capturing the Birds

RMBO biologists first needed to capture tanagers and thrushes in the park and equip them with geolocators, tiny devices that would track their journey. But both species came with challenges. Male Western Tanagers, with vibrant yellow feathers covering their body, black wings and a bright red-orange head, can be quite shy and inconspicuous, making them difficult to capture despite their vivid markings. The songs of Swainson’s Thrushes are often heard in the forests of Rocky Mountain National Park, but catching a glimpse of and capturing this secretive species is an ambitious task.

Not to be deterred, the biologists sought out the birds’ territories, areas being defended and used by the males, equipped with mist nets, decoys and devices to broadcast calls. They set up the mist nets and used carved wooden replicas and recordings of the males’ calls to draw out other male birds defending their territories. If successful, the birds would swoop in to investigate the unknown male and fly into the mist nets. Using this method, the biologists captured 10 Western Tanagers, but Swainson’s Thrushes weren’t so easily deceived and none of this species was caught in the summer of 2012.

C’mon! Fly into the net! A live male Western Tanager perches in a tree above a wooden decoy of a male tanager, with the mist net barely visible in the background.

Once the biologists captured the Western Tanagers, they placed a band on the birds, outfitted them with a geolocator and released them back into the wild. In the fall of 2012, the tanagers migrated with the geolocators attached to them like a miniature backpack, weighing up to one-and-a-half grams (including harness materials). As they migrated, light intensity measurements were taken twice a day and recorded on the very small but hardy devices.

RMBO biologist Greg Levandoski attaches a geolocator to a male Western Tanager, which the bird wears like a miniature backpack.

A geolocator is visible on the back of a Western Tanager prior to the bird’s release back into the wild.

Recapturing the Birds

Catching the Western Tanagers the first summer was tough work, but the biologists had to recapture the birds the following summer to retrieve the geolocators – and the precious data they contained. Fortunately, in 2013, the biologists knew where to start to look for them, where the tanagers were captured in 2012. With a little luck, a great deal of experience and the help of technicians, they were able to locate four of them, identified by their leg bands and geolocators. Spotting them was a great feat, but the biologists had to persuade the birds to fly into mist nets again to be recaptured.

“The second year it seemed like they had learned,” Jason said. The call system and decoys didn’t seem to be as enticing as the year before, and the birds took a little more coaxing this time. With a little extra effort, two of the four birds were caught and their geolocators removed. Jason said getting two of the original 10 was a success and his team was happy with the outcome.

Success! This Western Tanager was recaptured in 2013 and its geolocator, visible in this photo, was removed.

Revealing the Migration Route

With two geolocators recovered, GIS Manager Rob Sparks analyzed and interpreted the data on the devices. The geolocators took light intensity measurements twice a day, which Rob used to find the latitude and longitude of the birds’ locations by comparing to the different times of sunrise and sunset in different areas. With these data, the coordinates of the birds could be identified with an accuracy of up to 100 miles, which isn’t bad considering the total distance the birds traveled.

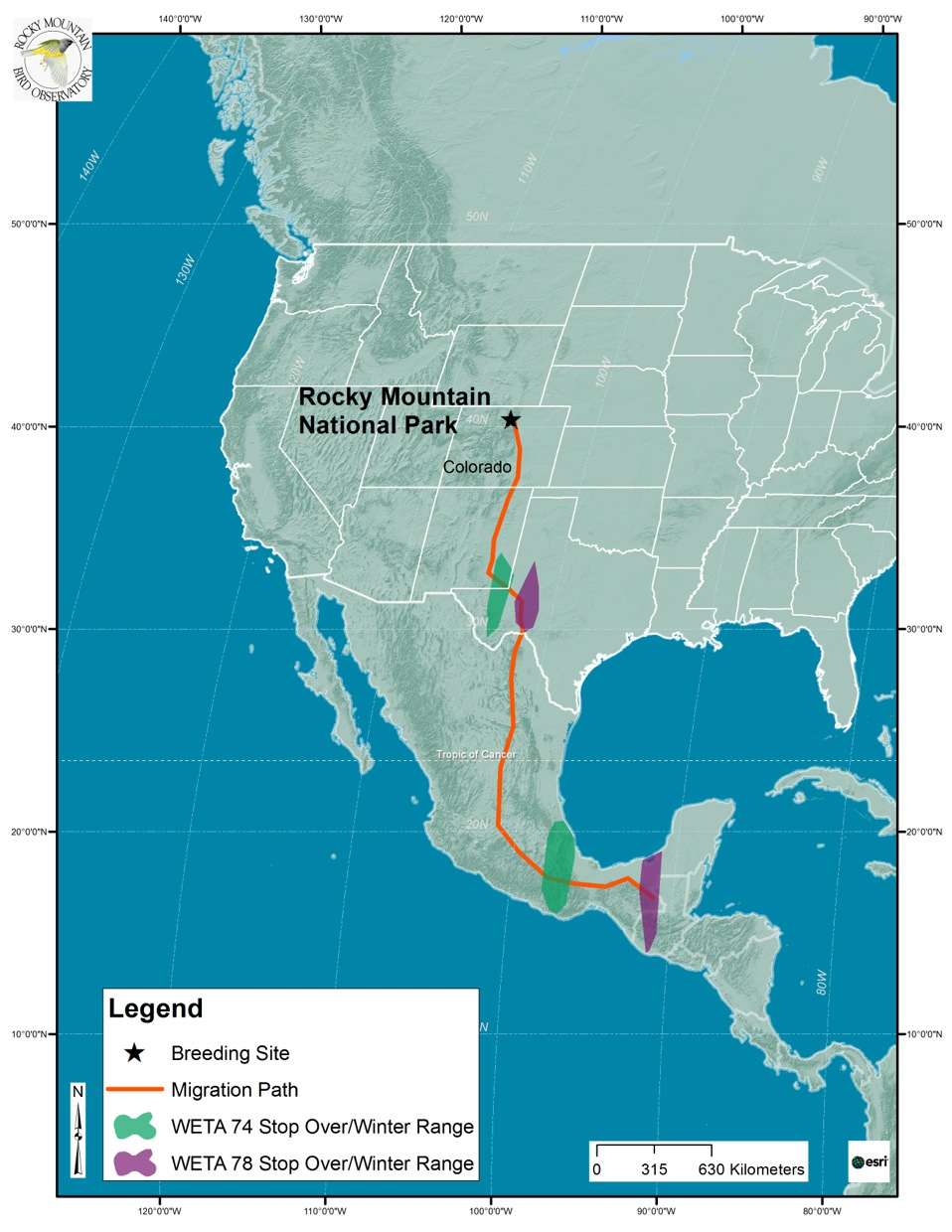

Western Tanager Migration Map

As expected, the two Western Tanagers underwent a molt migration. Western Tanagers are one of the few species that take an extended stopover during migration to not only rest and refuel, but grow new feathers. It’s almost like planning a layover flight in order to change clothes. The two Western Tanagers stopped over in west Texas and southeastern New Mexico to molt, staying about a month to grow new feathers and take advantage of the burst in insects and vegetation during monsoon season.

With full bellies and a glossy new winter look, the birds continued on their journey to complete their migration. The two birds traveled to southern Mexico and northern Guatemala for the winter, where they stayed until the following spring and their return to Rocky Mountain National Park. Jason said that knowing the approximate migration route of Western Tanagers from Rocky Mountain National Park, as well as their stopover sites, is vital for conserving these migrants.

~ Marina Rodriguez, Colorado State University student, CO301B: Writing in the Sciences

Editor’s Note: In June of 2014, the team from RMBO and retired National Park Service biologist Jeff Connor returned to Rocky Mountain National Park to look for the two banded tanagers spotted but not recaptured in 2013, or other Western Tanagers banded during the summer of 2012. Despite several days of searching, they were unable to spot the birds. But they did have success with a thrush! While in the park in the summer of 2013 to recapture the tanagers, RMBO biologist Greg Levandoski managed to capture a Swainson’s Thrush. The bird was outfitted with a geolocator. In 2014, the bird was recaptured and its geolocator retrieved. GIS Manager Rob Sparks is currently analyzing the data on the geolocator to determine this thrush’s migration route, stopover sites and wintering grounds.

Taking no chances, RMBO’s Greg Levandoski removes the geolocator from a Swainson’s Thrush still in the net while Jeff Connor, retired National Park Service, watches. The thrush was outfitted with the geolocator in June of 2013 and recaptured in roughly the same location in Rocky Mountain National Park in June of 2014.