Female and male Black-throated Blue Warbler, and me! Photo: Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, 2015.

My name is Brandt Ryder. I am the new Science Director at Bird Conservancy of the Rockies and this is my personal story. It is the story of what motivates me and why I have devoted my life to conservation. We all have people in our lives who have altered our course and shaped who we are, this is the story of those people.

A beautiful day in Western Massachusetts, not far from my Grandfather’s farm.

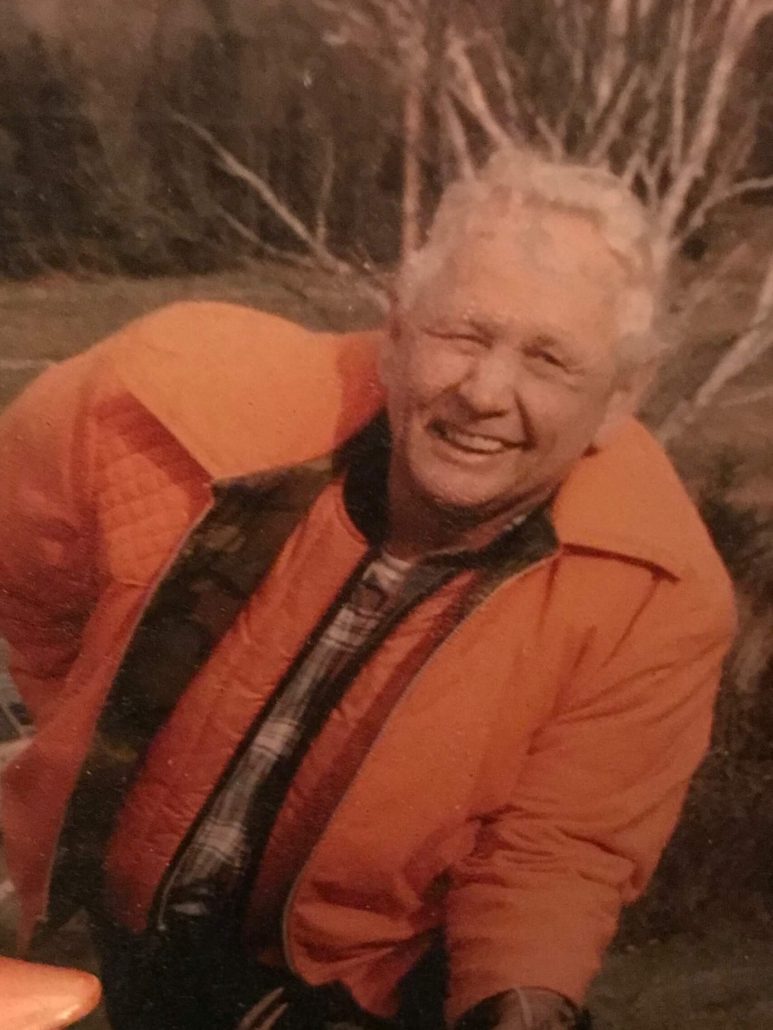

I was born and raised in eastern MA about 45 minutes west of Boston. As a child, I spent a lot of weekends traveling to Western MA to visit my grandfather’s dairy farm. My grandfather, Floyd, was a stern character and the hardest working person I have ever met. Despite his stern nature, he had a way with kids, and he loved his grandchildren more than anything else. Floyd was an avid outdoorsman, spending his free time walking his land, hunting and fishing. He lived off the land and he understood that stewardship was essential to his livelihood, making him the first conservationist that I ever met. When I was about 5 or 6, my grandfather started taking me for nature walks. He taught me how to read the history of a landscape by pointing out markers of time like lonely old wolf trees. He taught me my first bird songs, the flute-like chorus of the Wood Thrush and the raspy song of the Scarlet Tanager.

The Wood Thrush has been a part of my personal journey since the early days — from learning its song from my Grandfather as a kid, to later helping research the reasons behind population declines while working at Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (SMBC). Photo: Bob Devlin Flickr CC by 2.0

Floyd was a beacon of light and a source of inspiration to everyone around him. He used to say, “Be the person you want to be, not the person the world wants you to be.” As my grandfather aged and shut the doors on his dairy farm, he ensured his conservation legacy by putting large tracts of his farm into conservation easements. On a late winter morning during my sophomore year in high school, Floyd died of a sudden heart attack while shoveling snow. As a preoccupied teenager, I had largely forgotten about those nature walks, but in his absence, those memories came flooding back. Because of my grandfather’s influence, I went onto major in wildlife biology at the University of Massachusetts.

Floyd Ryder was a larger-than-life character who loved his land and imparted a vital stewardship ethic in our family.

As I advanced in college, I became keenly interested in birds. One summer I decided to drive back and visit my grandfather’s farm in western Massachusetts. Like me, the forest had aged, matured. It was still as amazing as I had recalled from my childhood memories, except for the birds. The once musical landscape was now quiet. I chalked it up to my inexperience as a birder—or that my childhood memories were larger than life. In retrospect, my observation was probably accurate. Birds were and are continuing to disappear from our forests and fields at an alarming rate. Recent evidence suggests we have lost 3 billion birds since 1970 and my experience was a microcosm of a worldwide phenomenon.

Will spectacular beauties like this male Bullock’s Oriole still be around for future generations? Yes, if we take action! Photo: Kevin Cole Wikipedia CC by 2.0

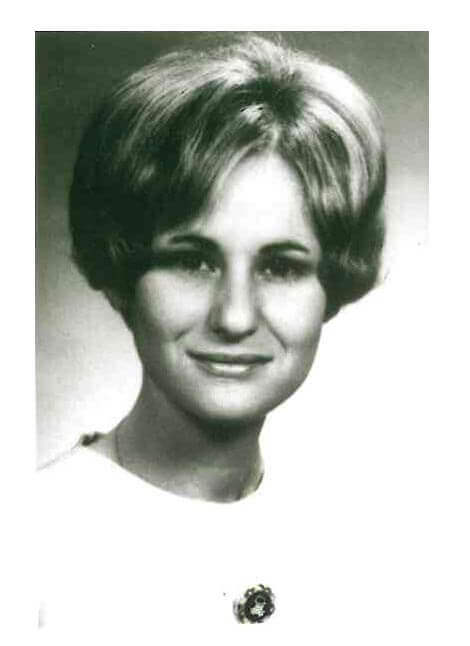

After college, I met my now wife, Julia, and she quickly introduced me to her mom, Harriet—or Gracie, as we called her. Gracie became my biggest champion. She always told me I could be or do anything I wanted as long as I made a difference. She inspired me to always shoot for the moon. In 2012, Harriet passed away after a long battle with cancer. Four years later in April of 2016, my daughter Wren Grace Ryder was born. Gracie never got to meet Wren, but her spirit is so apparent in her.

Harriet (Gracie) Feder was another major inspiration in my life who fostered a desire to make the world a better place.

The passing of Gracie and the birth of Wren dramatically changed my personal and professional perspective on life. This was a moment of awakening. I had spent the better part of my career in an “ivory tower” publishing scientific papers. These actions and outcomes, however, rang hollow. I wasn’t being the person I wanted to be, and I wasn’t making a difference. I knew my legacy must include positively affecting change through conservation action. I knew I wanted to make the world a better place for my daughter, a world with birds.

I joined the staff at Bird Conservancy because not many organizations have a holistic view of conservation. I like to think of effective conservation as a three-legged stool. Those legs are sound science, effective stewardship, and experiential education. We need science to make data-driven decisions. What are the mechanisms underlying the disappearance of birds worldwide, and what are the most effective conservation approaches to deal with threats? We need stewardship because people play an essential role in ecosystems. Our decisions and actions matter and very few organizations embrace the human dimensions of conservation. Education builds a conservation ethic in our children, teaching them that they are the scientists and stewards of the future. Floyd and Gracie are gone, but their legacy lives on in me—and my daughter Wren.

I am thrilled to be part of a special kind of organization. Let’s roll up our sleeves and do good work!

Banding a hatch-year female Rose-breasted Grosbeak. Photo: Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, 2015.

Brandt Ryder earned a Bachelors of Wildlife Biology from Unity College in (1999) and then went on to get a Ph.D. from the University of Missouri-St. Louis in (2008). Brandt’s dissertation focused on the demography and social behavior of a tropical lekking birds. Prior to joining Bird Conservancy, Brandt worked for a decade as a research scientist for the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center focusing on the conservation and behavior of birds across their annual cycle. Brandt has published over 50 peer-reviewed papers on a diversity of topics including urban ecology, migration ecology, landscape ecology and behavioral ecology. Brandt enjoys the outdoors in his free time through hiking, running, and doing landscape and astrophotography. He can be reached via email or by phone: 970-482-1707 x 43