On a cool October night, a bundled-up researcher is working to gently extract a Northern Saw-whet Owl from a mistnet. Guided by the beam of a headlamp, the researcher plucks strands of netting from the grasp of the owl’s talons, then tugs a couple more strands up and over the wings, over the head and voila- the owl is free. In the background, the repetitive “toot-toot” of the owls’ song pierces the chilly air from a loudspeaker. The researcher pulls the owl close to their chest, then walks carefully upslope to a nearby tent, where a few of volunteers are eagerly hoping that this net check was fruitful.

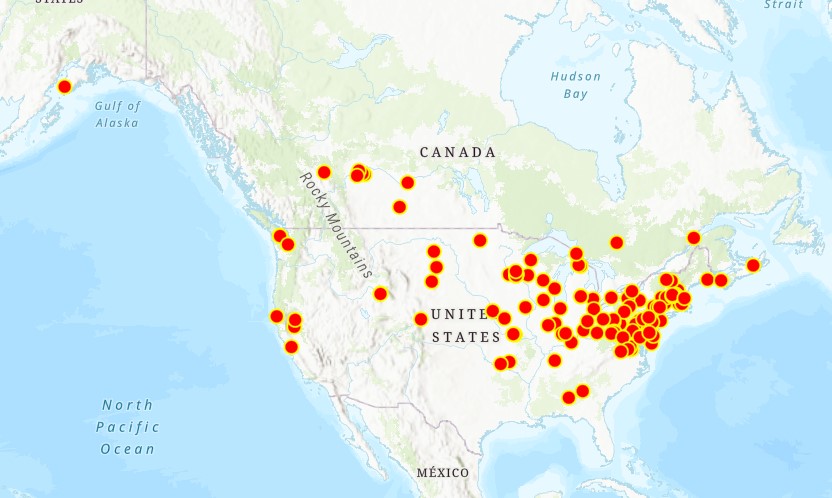

The researcher- Marion Clément, Jessie Reese, or Brandt Ryder, depending on the night, are all Bird Conservancy of the Rockies staff that devote some late nights to shed light on these elusive owls. Although this banding station above Bellvue, Colorado, is one of a few along the Front Range of the Rockies, it is nested within a robust network of owl banding stations that share a passion for learning more about this little migratory owl. Together, these banding stations are working to amass a truly impressive dataset, with more than 400 thousand Northern Saw-whet Owls banded and approximately 13 thousand banding recoveries (banded owls re-sighted further down the line). To put these numbers into perspective, the Bird Banding Laboratory reports that American Barn Owls, which are the second most-banded owl, has had 103 thousand individuals banded in the USA and Canada combined since the 1960’s. Northern Saw-whet owls are the most banded owls in North America by a landslide.

Northern Saw-whet Owls have been called a “gateway drug to conservation” by ornithologist and author Scott Weidensaul. When the volunteers spot the little owl in the hand of the researcher, it’s easy to see why. Pupils widen, smiles break out, and “oohhhs” and “awws” are abound; it’s hard to resist the charm of this owl. In the center of a fluffy round head perched atop a smaller body, two beautiful round eyes adorned with long black eyelashes stare right back at its audience, occasionally softly blinking. The owl’s demeanor is calm, as if it’s done this before and understands the significance of this moment. But the owl is not banded, so we can assume this is its first time in a human hand. While the audience gushes, the researcher gets to work on weighing and measuring the owl, then places an aluminum band with a unique number on its leg.

There was a time when banding birds was one of the best ways to learn about avian species on a large scale. Recovered bands (such as those from photographed, recaptured, or rehabbed birds) provide two location points on a timeline of a bird’s life. Two points is not a lot of data to work with, but amassed across thousands of bands and recoveries, researchers can start to get a picture of population trends, survival rates, and migration pathways. Nowadays, newer technology involving electronic tracking devices, such as radio telemetry, satellite or cellular transmitters, and the Motus network, is revolutionizing our understanding of avian ecology. But owls, especially those small species like the Northern Saw-whet Owl, are still at the fringe of our ecological studies. Northern Saw-whet Owls weight about 90 grams (about the same as a small bar of soap), requiring lightweight transmitters; they are nocturnal, prohibiting our ability to use solar panels to power tracking devices, and most importantly, they are nomadic, rarely returning to the same breeding or wintering ground. All of these traits make their study particularly challenging, so banding data remains a cost-effective way to assess their conservation needs and status.

If I had to venture a guess for the proportion of bird enthusiasts or biologists that once visited a Northern Saw-whet Owl banding station, I’d venture about half. For such a small owl, the Northern Saw-whet Owl has such a large impact. Across North America, banding stations mostly run by volunteers invite friends, students and the public to witness the ritual of the catch and release of these owls late at night. It makes a lasting impression, inspiring some to devote their studies to wildlife, some to donate to conservation and others to turn off the lights during migration or avoid rodenticides in their home. The same captivation is what led to a growing network of banders in the 1960’s to stay up past their bedtime and band this owl. At the time, Northern Saw-whet Owls were believed to be rare and nonmigratory, but emerging data from these stations revealed otherwise. As more researchers took interest in this owl, it was evident that in order to produce good data we needed some standard protocols in place. David Brinker, one of several researchers enamored by this owl, saw this need and acted: and thus Project Owlnet was born in 1998. This email listserv was originally intended by Brinker to be a platform to share ideas and methods, but it rapidly grew into a network of 150 active banding stations that continue to share data, methods and ideas.

Under the condition of their federal bird banding permit, banders must submit yearly banding data to the Bird Banding Lab; this includes band numbers, date and location of capture, and morphometric measurements. This data is standardized, proofed and archived in a publicly accessible database. But what isn’t captured in this dataset is effort data- the number of owls that are caught per unit of time and net area. As the network of banding stations has been exponentially increasing since the start of Project Owlnet- this data is just as important as the archived banding data. In addition, effort data contains crucial information about variation of operating procedures between banding stations. This dataset is essential to produce robust estimates of population trends, yet it is stored by individual banding stations in different formats and is at risk of loss.

Now in the 30th year since the start of Project Owlnet, Bird Conservancy of the Rockies and Project Owlnet are working together to address the risk of data loss and to improve the accessibility of this data. Thanks to some generous donors and a grant awarded by the Conservation Fund of Tracy Aviary, we have made strides towards the future of Project Owlnet. Our goals include (1) the creation of an up-to-date list of our collaborators through a registration form, (2) the creation of a working group to steer the next priorities for the network, and (3) the creation of a database entry and archiving platform that will facilitate future analyses. All of this will be accomplished with the input of collaborators, to make sure we are capturing their broader interest and ensure their commitment in this effort.

With the help of the working group, we’ve identified an exciting avenue for the database repository. We are working with Nature Counts, a data platform from Birds of Canada that facilitates reliable data collection and archiving. We hope to have some exciting new tools to share with the Project Owlnet network, so stay tuned! To learn more about Northern Saw-whet Owls and Project Owlnet, check out this webinar of Scott Weidensaul hosted by Bird Conservancy of the Rockies.

Back at our banding station, a Northern Saw-whet Owl is ready for release. Gently placed on the palm of a volunteer’s hand, it waits for its eyes to adjust to the returned darkness by looking around at its audience. Several people whisper and marvel at the owl’s beauty, taking a few blurry photos illuminated only by a red light. The owl returns its gaze to the darkness, lets out a little white wash to bid its handler good luck, and lifts effortlessly into the night. We bid it good luck on its migration, and return to our blind, eager for the next net check.

This article was written by Marion Clément, Senior Avian Ecologist and Mexican Spotted Owl Coordinator