Aplomado Falcon monitoring highlights the importance of Chihuahua for population recovery in the southwestern US.

.

Aplomado Falcon. Photo © IMC Vida Silvestre

Bird Conservancy of the Rockies works with the Mexican conservation organization IMC Vida Silvestre and Mexico’s Sonora State University (abbreviated as UES in Spanish) to monitor and conserve the Northern Aplomado Falcon (Falco femoralis septentrionalis) population in the Chihuahuan Desert, which is in imminent danger of extinction. The species is listed as Endangered in the U.S. and Threatened in Mexico. 1 This tiny population is currently restricted to the central part of the state of Chihuahua, Mexico. Note that other populations of this subspecies (the reintroduced population in South Texas and the natural population from Veracruz, Mexico through Central America) are faring somewhat better.

Rodriguez-Salazar uses a mirror to monitor a nest for eggs or chicks. Photo © IMC Vida Silvestre

Roberto Rodriguez-Salazar of IMC Vida Silvestre and Dr. Alberto Macías-Duarte (now at UES) have been monitoring the population since 2002 and 2000, respectively. The Peregrine Fund originally started the monitoring program, and Bird Conservancy of the Rockies got involved in 2013. CONANP (Mexico’s National Commission for Protected Natural Areas) also supported the project for a few years. Current funding supports the monitoring of 20-30 historic and active breeding territories in Chihuahua each year. In each of the past few years, 8-14 territories have documented breeding pairs, of which only 5-8 pairs are usually successful, producing 10-17 fledglings per year.

Successful fledglings on a yucca, the preferred plant for nesting. Photo © IMC Vida Silvestre

Nesting success is limited by nest predation (mainly by Great Horned Owls), drought and the ever-shrinking grassland habitat for nesting and hunting. Many cattle ranches in and around falcon breeding territories are being converted to irrigated central pivot crop fields due to strong demand from farmers for land to grow cotton and other commodities, and little enforcement of regulations controlling land-use change and well drilling. The situation also exposes falcons to increased pesticides via their consumption of prey. Most of the ranches that remain in cattle production are experiencing habitat degradation, especially from shrub encroachment. Northern Aplomado Falcons require grasslands with less than 10 percent shrub cover 2. Drought is another threat to survival and is anticipated to increase in the Chihuahuan Desert with climate change (Macías-Duarte et al. 2016).

Google Earth shows green central pivot crop circles taking over core areas of the Northern Aplomado Falcon population range in Chihuahua, such as the Tarabillas Valley (bottom right crop circles).

Close-up of cropland conversion; the right side of the fence line shows the high-quality grassland that was lost on the left side of the fence. Photo © Greg Levandoski

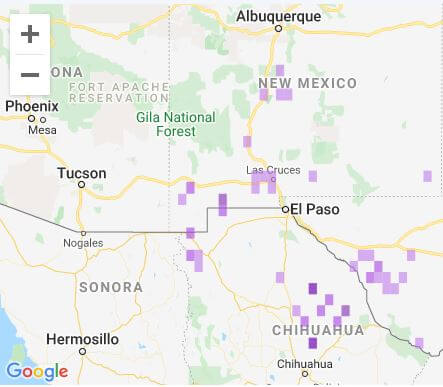

Northern Aplomado Falcons are occasionally observed in southern New Mexico and West Texas, where they were common in the 1800s and also once common in southeastern Arizona 3. Some of those U.S. sightings in the 2000s and early 2010s could be birds from reintroduction attempts that failed 4. Note that the South Texas Gulf Coast reintroduction by the Peregrine Fund was successful, but likely too far away for those birds to reach New Mexico or west Texas). Any birds observed outside of the reintroduction period (2002-2012) are likely Chihuahuan in origin. Meyer & Williams (2005) cite a bird originally banded in Chihuahua and observed in New Mexico in 1999 as evidence of dispersal of young birds from Mexico.

eBird observations of Northern Aplomado Falcons; note that there are few observations in Chihuahua likely due to much lower eBird participation in Mexico than in the U.S.

Macías-Duarte and Rodríguez-Salazar are conducting a demographic study with bird banding and satellite telemetry, funded by US Fish and Wildlife Service, that provides further support for dispersal from Chihuahua. The results of this study will be published in the Journal of Raptor Research in 2021.

Alberto Macías-Duarte, assisted by Nancy Hernandez-Rodriguez of IMC Vida Silvestre, measures falcon chick for demographic study. Photo © IMC Vida Silvestre

As part of the study, a satellite transmitter was placed on a juvenile Northern Aplomado Falcon in the Municipality of Ahumada, Chihuahua in May, which traveled to New Mexico in mid-July, where it has remained near Lordsburg, perhaps searching for a future breeding site.

Google Earth map of the journey (red arrow) of the adventurous juvenile from the population in Chihuahua (blue circle) to its current home in New Mexico (magenta circle)

This dispersal event of a Northern Aplomado Falcon from Mexico to the United States is of great importance because:

- It increases hope for restoring the species in parts of its historical range in the southwestern U.S. If the Northern Aplomado Falcon could recolonize the US, it would improve the chances for this endangered population’s survival since it has lost so much habitat in its current range in Chihuahua. Meyer & Williams (2005) documented four nests (one successful) in New Mexico 2000-2001 that also provide hope for reestablishment. Hunt et al. (2013) are not optimistic due to the lack of success of the reintroduction programs in New Mexico and West Texas, but this failure could have been due to the use of falcons from populations along the Gulf Coast of Mexico that might have not been adapted to desert conditions, so it may be possible that the current landscape of southern New Mexico and West Texas could still support falcons recolonizing these areas from within the Chihuahuan Desert.

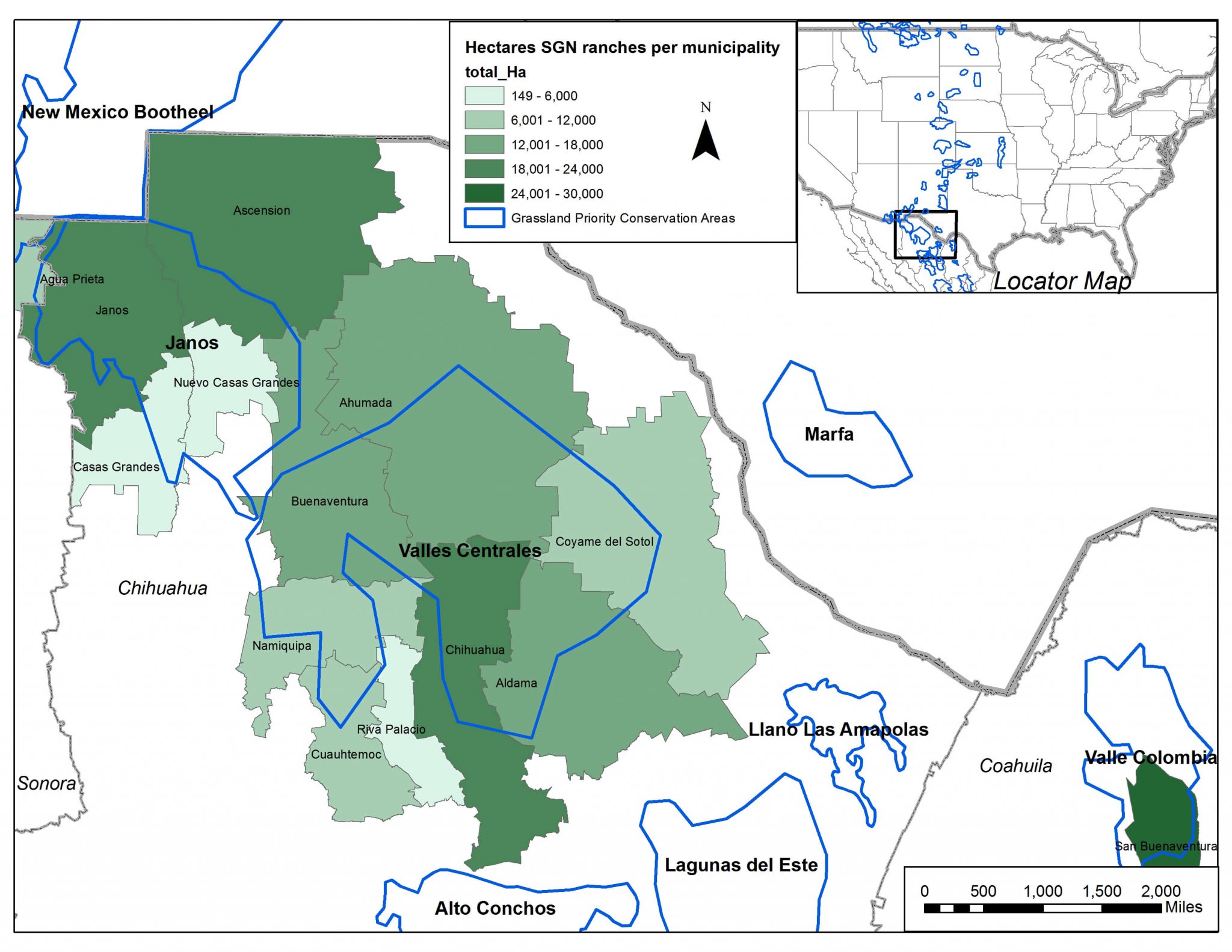

- Juvenile dispersal patterns can tell us where we should focus efforts to conserve grassland habitat. IMC Vida Silvestre and Bird Conservancy promote a Sustainable Grazing Network (SGN) of cattle ranches in northern Mexico, a few of which this bird traveled through on its journey north, indicating these ranches provide suitable habitat.

Map showing the distribution of ranches enrolled in Bird Conservancy and IMC Vida Silvestre’s Sustainable Grazing Network (SGN) across municipalities in northern Mexico that support grassland bird conservation.

State-of-the-art technologies can support conservation and with these data and ongoing tracking efforts we will continue efforts to protect the source population in Chihuahua, as well as new breeding sites as they are discovered, targeting conservation actions. These actions include:

- 68 covered nesting cribs that reduce predation

- 172 stock tank escape ladders where falcons and other birds can get a drink without drowning

- 4,628 acres of shrub removal and 1,479 acres of subsoiling treatments to restore grasslands habitats and bird communities

- range management support for the sustainable and profitable operation of cattle ranches and the conservation and regeneration of healthy grasslands

- cost-sharing for ranch infrastructure and grassland restoration to support ranch operations and keep working ranches in the black so they don’t have to sell or rent land for row crops

Falcons in nesting platform behind water tank with escape ladder for them to perch on while drinking. Photo © IMC Vida Silvestre

These conservation actions are possible thanks to the generous support* of Bobolink Foundation, USFWS, the Bureau of Land Management, US Forest Service, and the Southern Wings Program of the Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies.

*different funders support different conservation actions

References:

- Macías-Duarte, A., Montoya, A. B., Rodríguez-Salazar, J. R., Panjabi, A. O., Calderón-Domínguez, P. A., & Hunt, W. G. (2016). The imminent disappearance of the Aplomado Falcon from the Chihuahuan Desert. Journal of Raptor Research, 50, 211-216.

- Meyer, R.A. & Williams, S.O. III. (2005). Recent nesting and current status of Aplomado Falcon (Falco femoralis) in New Mexico. North American Birds, 59, 352-356.

- Keddy-Hector, D. P., Pyle, P. & Patten, M. A. (2020). Aplomado Falcon (Falco femoralis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Hunt, W. G, Brown, J. L., Cade, T. J., Coffman, J., Curti, M., Gott, E., Heinrich, W., Jenny, J. P., Juergens, P., Macías-Duarte, A., Montoya, A. B., Mutch, B., & Sandfort, C. (2013). Restoring Aplomado Falcons to the United States. Journal of Raptor Research, 47, 335-351