If you walked along the banks of any river in North America a mere 400 years ago, you would likely have stumbled upon vast shallow pools of water lined with willows, sedges, and other wetland grasses and forbs. Kingfishers sat on tree limbs overlooking the water while herons dipped their toes in the shores. A Wood Duck flew whistling past and Common Yellowthroats sang “wichity-wichity” as they defended their territories. You may have seen a maze of connected swamps with nothing but a trickle of water connecting one area to another, or you may have seen cascading pools with logs and sticks holding the water back. Looking more closely you may have noticed key similarities within each pool. Each had a dam on the lower end, some short and squat and spanning a small stream, others tall and long and spanning an entire flood plain. These dams and the waters behind them were not placed there by accident. They were created by some of evolution’s greatest ecosystem engineers: beavers!

A beaver dam in Morgan County, Colorado. Photo by Kelsea Holloway.

On the Brink of Extermination

Beavers have had a rough history in the United States. Before European colonization, there were 60-400 million beavers in North America1, but these numbers were reduced to near extinction by the 1900s, when conservation efforts began 2. During westward colonial expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries, their valuable fur made them a target for trappers. In addition, like many wildlife species, beavers have also experienced significant habitat loss. Wetlands were considered by lots of people to be a waste of good soil, so many were converted into farmland, and areas surrounding rivers and streams were largely dedicated to ranching and development or operations. This led to a lack in woody vegetation for forage and dam building which beavers needed to survive.

A beaver dam across the Lower South Platte in Sedgwick County, Colorado 2021. Photo by Kelsea Holloway.

Benefits of Beavers

Due to years of observation, research and the acknowledgement of our mistakes, we now have a much greater understanding of beavers and the numerous ecological and societal benefits they provide. By damming the water and widening water channels, beavers help slow the flow, decreasing the potential of floodwater damage. Damming also allows sediment to settle out of the water column, resulting in increased wetland vegetation that filters chemicals and other pollutants and providing improved overall water quality. The pooled water also serves as surface and groundwater storage that provides a steady water source for downstream uses such as irrigation. Expanded wetlands also provide fire breaks in dry landscapes. In addition to these ecosystem services, these wetlands provide recreational opportunities like hunting and birdwatching, as well as diverse habitats for wildlife.

A beaver lodge on the Bijou Creek in northern Colorado. Beavers live and raise their young in lodges, which can only be accessed below the water. Photo by Kelsea Holloway.

Over 80 percent of wildlife visit riparian or wetland areas at some point in their lifecycle. In Colorado, 26 percent of the State’s 295 fish and wildlife species are considered wetland-dependent, with 78 percent of those species designated “wetland wildlife” 3. Invertebrates thrive in and around the water, reptiles and amphibians crawl and slither beneath the litter and low cover, small and large mammals bear young under the shrubbery, and birds hide in the thickets and perch in the tall canopies. Some species use these areas as stopovers for refueling on long migrations, while others are year-round residents. Without these habitats we would likely lose a lot of the animals we love.

Private Lands Wildlife Biologist Kelsea Holloway with ranch owners Tate McCoy and David Koffler (far right) near a beaver dam on their property in Morgan County, CO.

If You Build It, They Will Come

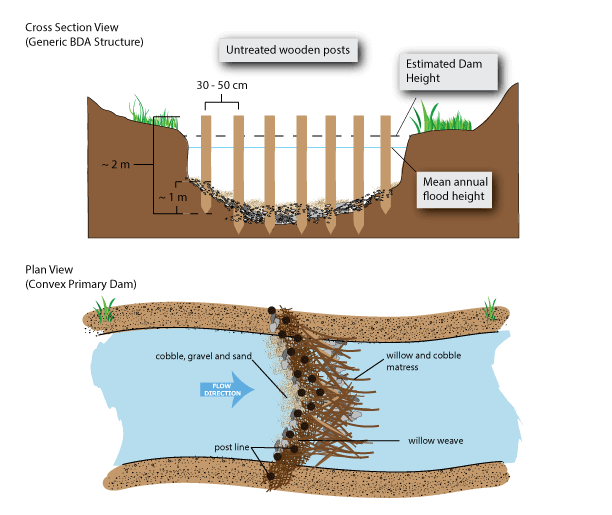

The first step in this process is to ensure that a given environment can support beavers. A water source, woody vegetation for dam and lodge building, and a steady food supply are all necessary. If these requirements haven’t yet been achieved in a given area, manmade structures that mimic beaver dams called Beaver Dam Analogs can be installed to promote beaver-friendly habitat and encourage beavers to occupy the area. Beaver Dam Analogs hold back sediment and debris, raise the groundwater level and reconnect creeks with their floodplains. Over time, these processes promote woody plant growth, allowing beavers to move back into the area and continue the wetland expansion themselves.

Beaver Dam Analog diagram from Anabranch Solutions. Credit: Elijah Portugal. (CC BY 4.0)

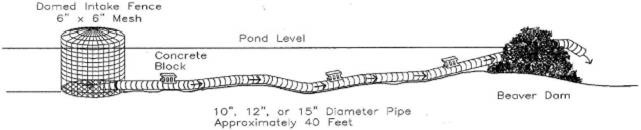

Despite the numerous benefits, beaver presence isn’t always celebrated. Beavers tend to dam any place they find with good habitat, which can include areas in culverts, near roadways, and in agricultural drainages. Backed-up water in these landscapes can cause hazardous flooding of developed areas. There is, however, a solution to this! Beaver Flow Devices are cost-effective, man-made devices that can help mitigate flooding caused by beaver dams. The structures allow beaver dams to remain in place while providing continuous water flow through the dam, allowing beavers to remain on the landscape and maintain wetland areas while simultaneously protecting human property.

A Beaver Flow Device also known as a Flexible Pond Leveler. Credit: Mike Callahan, Owner, Beaver Solutions LLC, “Working With Nature.”

Spreading Awareness

Kelsea is currently participating in an extensive training with the Beaver Institute, which includes building her own flow devices along the South Platte River. Her sites will serve as examples for beaver biology and management workshops offered landowners and land managers in late summer 2021 in northeastern Colorado. Kelsea is eager to demonstrate how beavers can be a natural solution to help maintain wetlands for birds and other wildlife, in addition to the other land management benefits they provide.

North American Beaver. Photo by Bill Hayden (CC0 1.0).

As beavers once again expand their territories throughout tributaries, wetlands, and rivers, humans can be allies. Learning about beaver biology and the ecosystem benefits they provide is a start. When you are bird watching, hiking, hunting or floating down a river, keep an eye out for beaver activity. A chewed tree stump, an interwoven dam of sticks, logs, and mud, or a what might look like a pile of mud with branches and grasses are all signs you are in a beaver territory. And this territory is on its way to becoming a thriving part of our ecosystem.

For more reading on beavers and their impact on North America and beyond try Eager, The Surprising Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter by Ben Goldfarb.

Kelsea Holloway (based in Greeley, CO) is employed by Bird Conservancy of the Rockies with funding support from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

Sources

- Crowe, D.M. 1986. Furbearers of Wyoming. Wyoming Game and Fish Department, Cheyenne, WY. Ringelman, J.K. 1991. Managing beaver to benefit waterfowl. Fish and Wildlife Leaflet 13.4.7. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

- Boyle, S. and S. Owens. (2007, February 6). North American Beaver (Castor canadensis): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region.

- CDOW. 2011. Statewide Strategies for Wetland and Riparian Conservation – Strategic Plan for Wetland Wildlife Conservation Program. Denver, CO.

Donate

Donate