George Whitten brings his love of ranching indoors with a toy cow resting on his windowsill

Water crisis in San Luis Valley prompts agriculturists to action

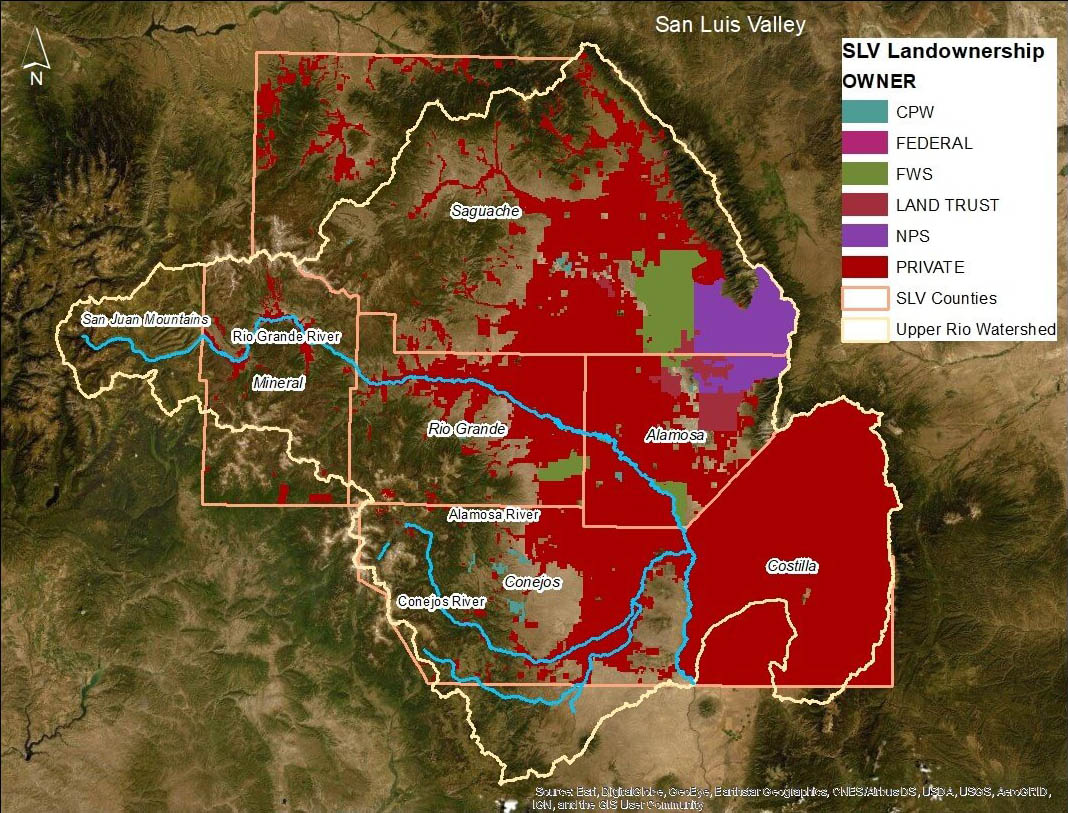

Water-related issues in the west are complex. From changes in natural water patterns to increased demands of human population and balancing the water needs of various stakeholders, there are no shortages of water problems to solve. Colorado is no exception. Across the state, many communities struggle to find solutions to ever-increasing issues of water scarcity. In the upper Rio Grande Basin, where a mere 7 inches of precipitation fall annually, landowners, organizations and agencies are collaborating to create sustainable aquifer levels for agriculturists, municipalities and wildlife.

Water above and below

Water that flows to the upper Rio Grande Watershed begins in the rugged San Juan Mountains, where rough mountain streams come together to form the sinuous Rio Grande River that is the lifeblood the San Luis Valley (SLV). The SLV’s hydrology includes more than meets the eye. It contains a unique hydrologic feature: a closed basin in the heart of Saguache County. The water flowing into the basin leaves either by evaporation or seepage into the ground. Just below the surface lies what was once an ancient lake and which is now is a nameless aquifer, providing what has historically been a consistent water supply to the otherwise dry valley. Despite not having a name, it has been vitally important to the people of this area.

Quiet communities sharing limited resources

When discussing water, it’s important to also talk about the people who rely on and protect the resource in question. Saguache County is made up of a series of quiet towns with stunning views. Community members live here because they love having access to recreation (especially hunting) and they appreciate the tight-knit community and feeling of solitude in an otherwise hectic world. Throw a dart on a map of the SLV and you will likely land on agricultural land. Many, like George Whitten, are multi-generational ranchers who must be increasingly creative in terms of managing their operations in a world where water resources are rapidly changing. Because the region is facing increasing water scarcity pressures, like much of the SLV, farmers and ranchers are key figures in creating solutions.

George Whitten doesn’t spend time bailing his hay, instead he piles it up and it stays fresh through the winter grazing season.

Adapting to challenges

In a world where water is scarce and margins are slim, agriculturalists struggle to stay in the black, much less be profitable. In a testament to human resiliency, they are adapting to the situation. For example, George is managing his cattle with progressive techniques to sustain the ecological value of his land while increasing the grass cover for his cattle. Additionally, he finds ways to make effective use of his water resources and host workshops about land sustainability. He also partners with wildlife organizations. George’s San Juan Ranch is Audubon Certified and follows bird-friendly conservation practices that aim to improve landscape health and productivity while also benefiting wildlife.

Many landowners are doing similar things. These are the boots on the ground, taking action and making tangible changes to achieve sustainability. Agriculturalists, along with many other stakeholders including agencies and organizations in the SLV, are working together to find solutions for long-term sustainability of water resources. With landowners leading these conversations, SLV stakeholders have created a system of self-taxation as an active approach to recharging the depleted aquifer. Agriculturalists are voluntarily agreeing to reduce their consumption of groundwater and at times fallow their own fields for the benefit of future generations of SLV inhabitants.

George Whitten talks about management of his pastures.

Shared resources, shared goals

This innovative leadership and collaboration creates opportunities for conservation partnerships some may view as “unlikely”, often facilitated by the Rio Grande Basin Roundtable. It may surprise many people to learn that agricultural and conservation goals are not so different. In the SLV, much of our most precious wildlife habitat for migratory birds of the Central Flyway is on working lands. These flood-irrigated grassy meadows are an oasis in the high desert providing habitat for hundreds of different bird species, like the Greater Sandhill Crane and the White-faced Ibis. By leveraging partnerships in the SLV, conservation organizations like Bird Conservancy of the Rockies and Natural Resources Conservation Service provide technical assistance, conservation planning and financial assistance to make restoration and habitat enhancements on these properties possible. We focus on finding win-wins for birds and the farmers and ranchers who have already made many personal sacrifices in the name of long-term sustainability.

Looking ahead

The work is far from over. Snowpack is sparse and water scarcity is not likely to change in the West. We’re continuing this important work by engaging all stakeholders and promoting the ecological benefits of progressive ranching management. The effort includes recognizing the efforts of landowners, paying homage where it’s due. With creative collaboration, communities in the Rio Grande basin have no plans of changing their focus. The hard work continues—uplifting our landowners, conserving our wildlife and carefully managing our precious natural resources.

This video premiered in March 2020 at the Monte Vista Crane Festival. We are grateful to partners Colorado Water Conservation Board, Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, the Monte Vista Crane Festival Committee, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, as well as Molson Coors, The Rio Grande Conservation District, Rio Grande Basin Roundtable, Colorado Parks and Wildlife Higel State Wildlife Area, and Friends of the San Luis Valley National Wildlife Refuges.

Emily’s position is supported in part by the NRCS Working Lands for Wildlife program, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife – Partners for Fish and Wildlife, and the Intermountain West Joint Venture.