Tip: To view the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies website in a language other than English, click “Accessibility Tools” and select the “Change Language” icon. ⤻

Tip: To view the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies website in a language other than English, click “Accessibility Tools” and select the “Change Language” icon. ⤻

[spacer height=”20px”]¡Qué chido!

Learning the Spanish vernacular of northern Mexico is a rewarding experience for many Bird Conservancy of the Rockies staff. Those who work on our international programs such as the Sustainable Grazing Network (SGN; Red de Pastoreo Sostenible), speak Spanish, but few started working for Bird Conservancy with prior knowledge of the slang (jerga) and vocabulary used in field work and ranching in northern Mexico. For example, “qué chido” means “how cool/ great” and is a common phrase in Mexico. During workshops and conferences with our partners, you can bet that this is often exclaimed as people share ideas about conservation and enjoy birding together in the Chihuahuan Desert grasslands.

Field crews from Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, Especies, Sociedad y Hábitat, A.C. and Pronatura Noreste, A.C. celebrate a successful training in the winter of 2021 in Chihuahua, Mexico. Video by Eduardo Sánchez.

The majority of North American grassland birds winter in the Chihuahuan Desert, two-thirds of which is in Mexico. This includes the states of Sonora, Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Durango, Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas. Although information on focal grassland bird species’ abundance and density is lacking on their wintering grounds, it is believed that the range of some species, such as the Baird’s Sparrow, is concentrated more greatly in Mexico than in the United States. Grants that fund grassland bird research are often focused on states and ecoregions within the United States, but it is crucial that we include Mexico as well and communicate in Spanish to best collaborate with partners. Bird Conservancy has long recognized that grassland bird conservation needs to take place beyond borders.

Communication is key

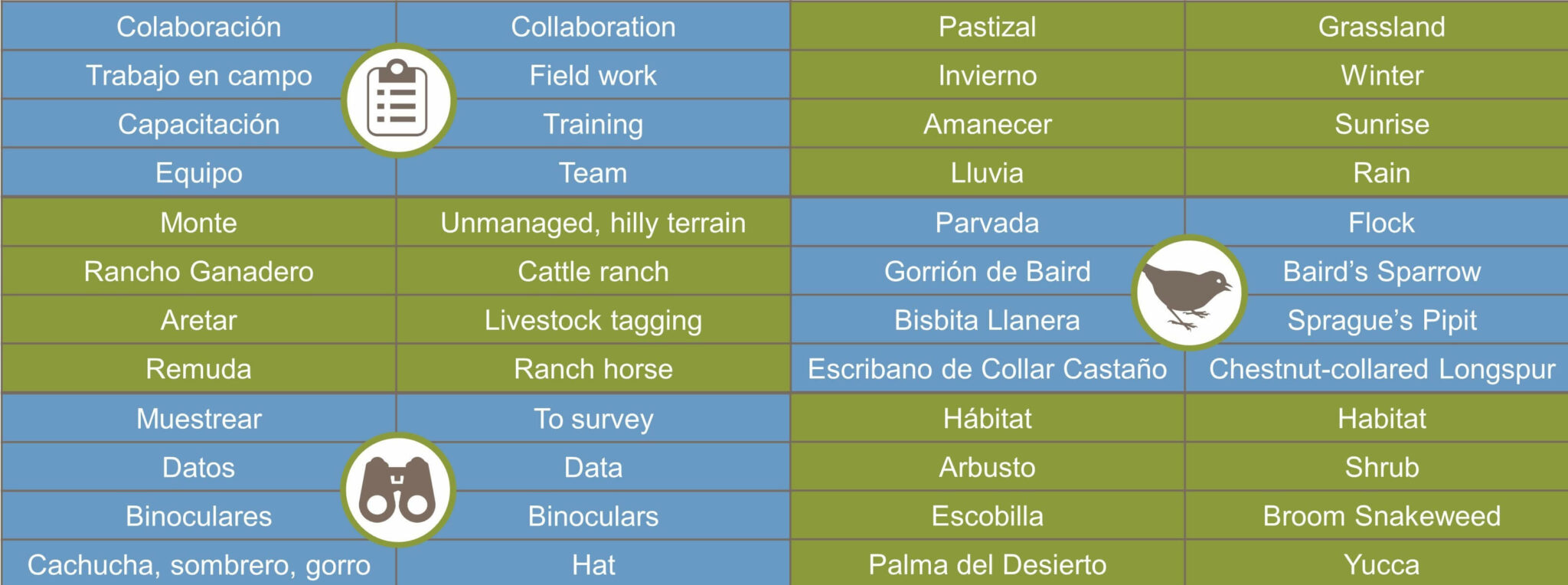

It is a fun challenge for Bird Conservancy staff to ensure that our communication in Spanish goes beyond generic fluency. In order to communicate around specific themes, provide effective trainings, and maintain relationships with the vast network of grassland conservation partners in Mexico, knowledge of certain vocabulary is crucial. See below for a few examples. Some words are used throughout Latin America and others are specific to northern Mexico. Some are similar in English and Spanish. Although we often refer to species Latin scientific names when working in English and Spanish settings, it is valuable to learn common names. For example, the Sprague’s Pipit Spanish common name includes “llanera”, which means inhabitant of the plains or prairie.

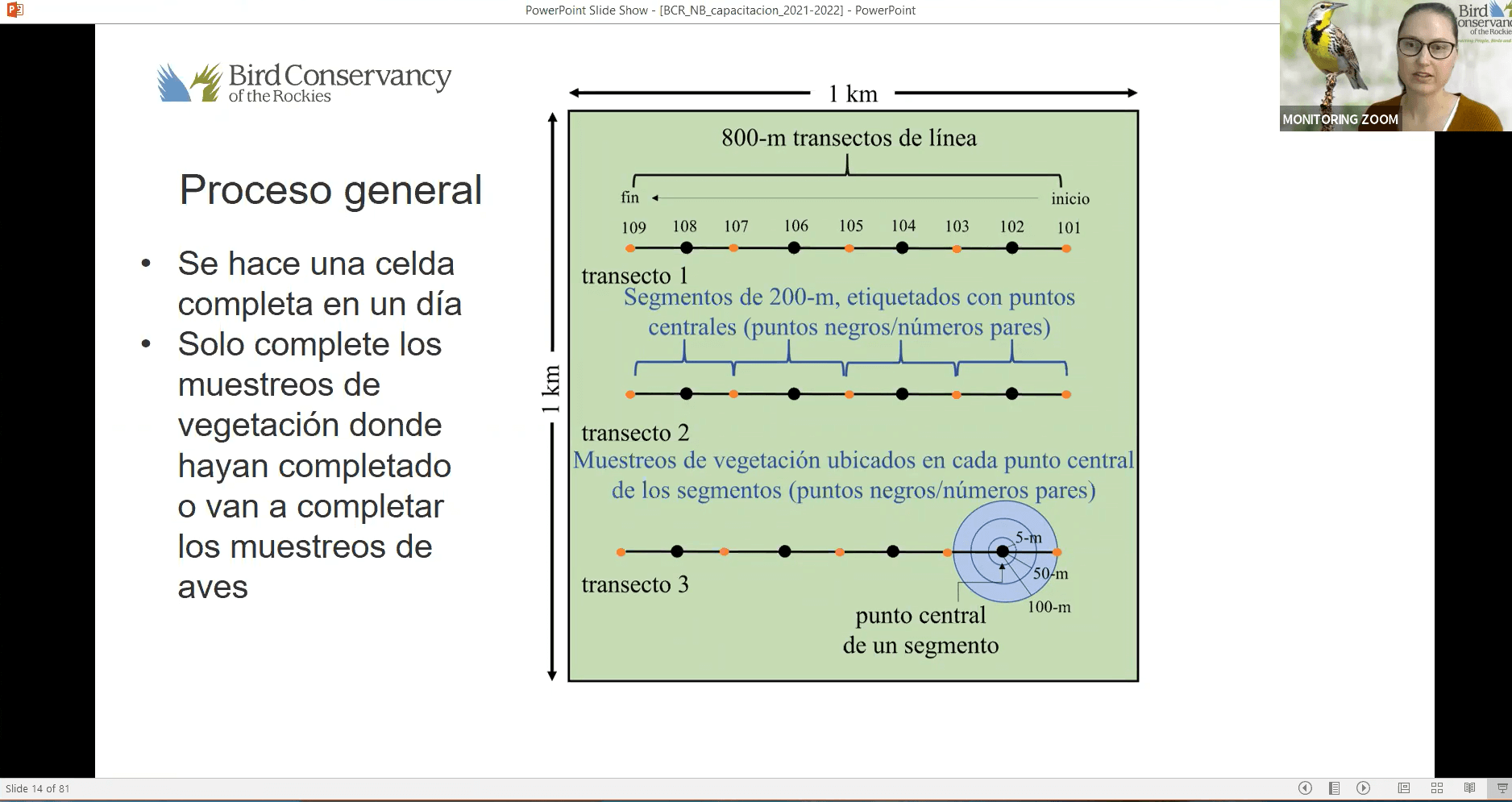

With up to 40 people from seven organizations involved in surveys, it can be challenging to train everyone at once and in the same location. We provide in-person trainings to field crews in Texas and New Mexico, in the United States and Chihuahua, in Mexico. We also provide virtual trainings. We work hard to provide the same protocols, datasheets, presentations, and resources in English and Spanish so that everyone collects data in the same way. When translating materials, we must consider that Spanish has grammatical gender, meaning that some nouns are categorized as either masculine (often ending in “o”) or feminine (often ending in “a”). With guidance from our partners in Mexico, we have included gender neutral language in the Spanish materials we provide in order to promote inclusivity. For example, rather than using “todos” (everybody), which despite being masculine, is also used for a group of people of mixed gender, we utilize “tod@s” or “todos(as)”.[spacer height=”20px”]

[spacer height=”20px”]

We use the same methods at all trainings to practice bird identification and calibrate habitat data collection. In Mexico, we are fortunate to provide trainings alongside experts at Especies, Sociedad y Hábitat, A.C. (ESHAC) such as Beto Rodríguez-Salazar, who has worked in the Chihuahuan Desert for many years and studies the Aplomado Falcon, and Alicia Juárez, a botanist who is the author of a guide to the plants of the state of Chihuahua. In Texas, the Dixon Water Foundation allows us to train on the Mimms Unit Ranch. This last season, we installed a Motus station on the ranch and field crews learned about our effort to develop the Motus wildlife tracking system across the Great Plains and Chihuahuan Desert.

[spacer height=”5px”]

[spacer height=”15px”]

[spacer height=”25px”]

Un éxito

This past 2021/2022 winter field season, our unified monitoring effort in the United States and Mexico was a success (un éxito). The program has grown since our 2018/2019 winter pilot season, 2019/2020 winter season in the Trans-Pecos, and 2020/2021 winter season which required a reduced effort due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We include both regional and ranch-level surveys in our study design and this season, we surveyed regionally in both countries for the first time.

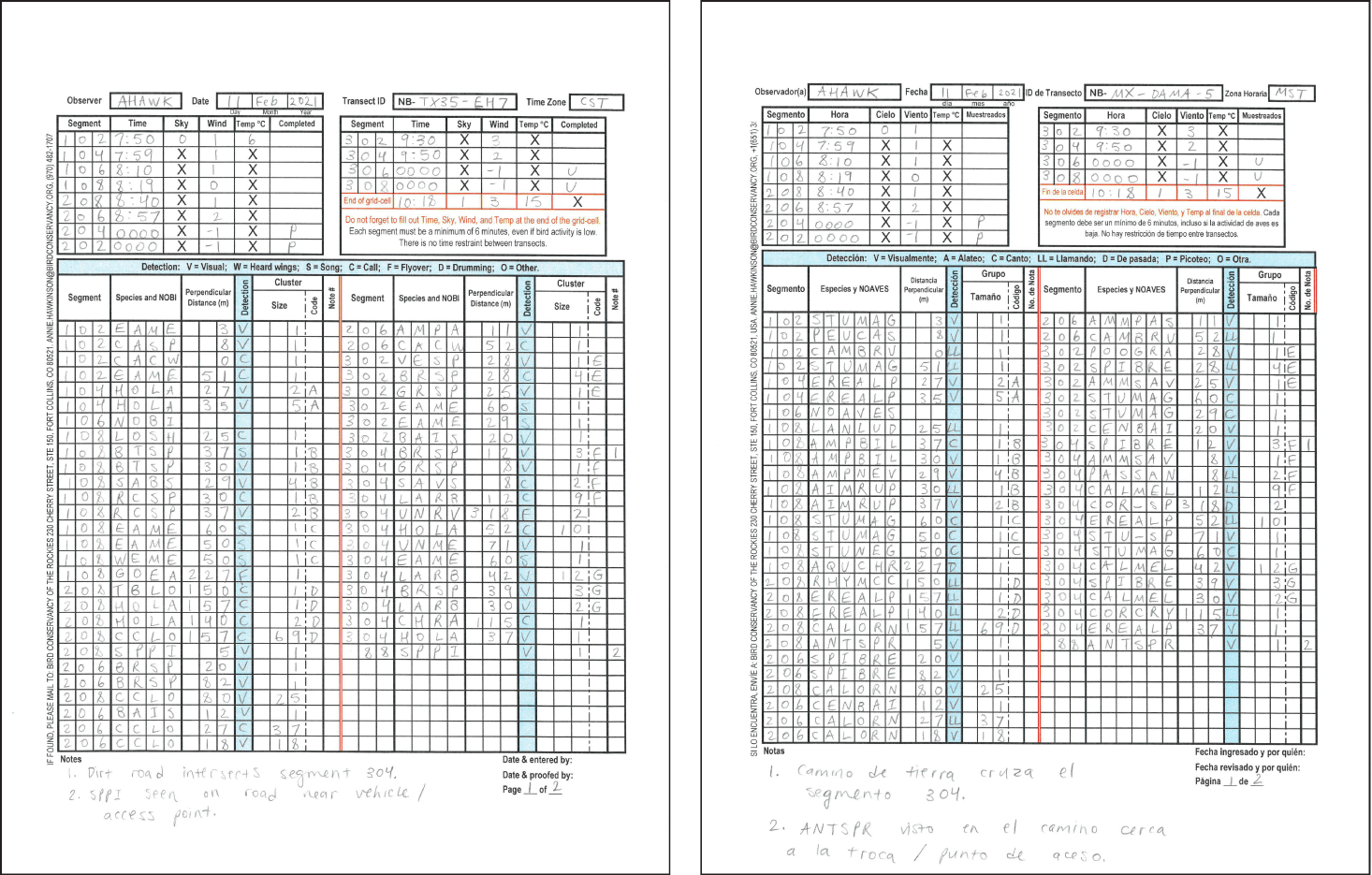

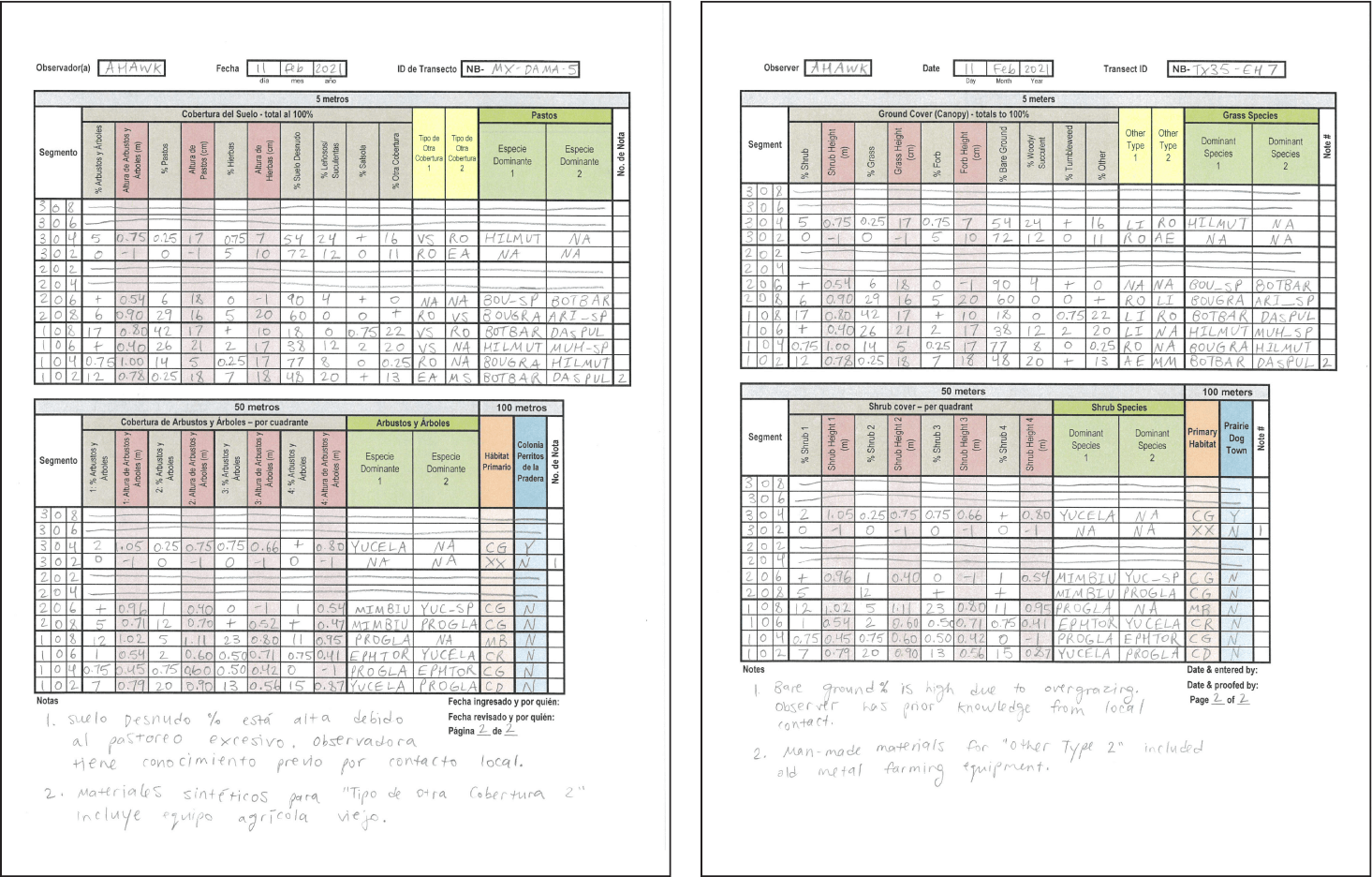

Example datasheets in English and Spanish

In Mexico, the ESHAC field crew surveyed two Grassland Priority Conservation Areas at the regional-level and 24 Sustainable Grazing Network ranches and ejidos (communal land), including shrub-encroached areas that have been restored to grasslands. The Pronatura Noreste, A.C. and Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango field crews surveyed one Grassland Priority Conservation Area and 19 ranches.

In New Mexico, the Bird Conservancy field crew surveyed 107 locations at the regional-level and 23 locations on two shrub-reduction study sites. In Texas, the Bird Conservancy field crew and the Borderlands Research Institute at Sul Ross State University (BRI, SRSU) field crew, led by graduate student Emily Card, surveyed 93 locations on private land and 120 locations on 5 ranch study sites. This impressive number of surveys is a testament to the dedication of the field biologists we rely on. With this large, consistent dataset we are establishing baseline population estimates for several species on their wintering grounds.

Across borders and languages, we plan to continue building the capacity of our wintering grassland bird monitoring program and working to inform the Full Annual-Cycle conservation strategies of grassland bird species in decline. ¡Hasta la próxima!

[spacer height=”20px”]

Funding for this program comes from The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation , Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and the Knobloch Family Foundation. Special thanks to the field biologists who cumulatively covered thousands of miles in 2021/2022, Especies, Sociedad y Hábitat, A.C. (ESHAC), Pronatura Noreste, A.C., Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, Borderlands Research Institute at Sul Ross State University, and Dixon Water Foundation. Thanks to Beto Rodríguez-Salazar and Eduardo Sánchez of ESHAC for additional support with this blog.