A biological bridge in Northern Colorado

There is a unique area in Northern Colorado near the Wyoming border where the mountains meet the plains. Against the backdrop of the Rocky Mountains, an arid and windswept foothills landscape transitions eastward to prairie where pronghorn, black-tailed jackrabbits and grassland birds are plentiful. This 200,000- acre mountains-to-plains region, known as the Laramie Foothills, is an important wildlife corridor connecting the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains with the High Plains of Colorado and Wyoming.

Pronghorn on Soapstone Prairie, photo by Mike Forsberg

This area is recognized by Colorado Parks and Wildlife, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Partners In Flight, the U.S. Shorebird Conservation Plan, The Nature Conservancy and other conservation groups as one of the highest priority conservation areas of the shortgrass prairie region. These lands support breeding populations of more than 20 high-priority bird species that have been steeply declining in numbers for the past 50 years, including Mountain Plover, McCown’s Longspur, Grasshopper Sparrow, and Colorado’s state bird, the Lark Bunting.

Male Lark Bunting in Soapstone Prairie, photo by Walter Wehtje

The City of Fort Collins, along with Larimer County, the Colorado State Land Board, local ranchers and private landowners have all partnered to conserve over 45,000 acres of this biological corridor, working together to manage it for grazing, recreation, natural resource extraction, and habitat management for grassland birds and other species. Bird Conservancy has monitored grassland birds here every year for the past 11 years. The annual data we collect helps to inform the real-time management decisions for the City of Fort Collins on these properties.

Collecting data using a point count survey method, photo by Erin Youngberg

A major keystone species in shortgrass prairie ecosystems is the Black-tailed prairie dog. These burrowing mammals generate disturbances that redistribute and recycle nutrients in the soil, increasing the types of plants growing around their colonies. Their grazing activity helps to increase the overall diversity of the shortgrass prairie by creating bare patches that are preferred nesting habitat for birds like the Mountain Plover, McCown’s Longspur and Burrowing Owl, and they act as a food source for birds of prey like Golden Eagle and Ferruginous Hawk.

Black-tailed prairie dogs on Meadow Springs Ranch, photo by Erin Youngberg

By studying and counting the types of birds we see, we gain insights into changes that are happening on the landscape. In the past 11 years, this area has seen some dramatic changes in the bird community as sylvatic plague has greatly reduced the populations of black-tailed prairie dogs across several colonies in the Mountains to Plains region. Where once we were detecting Mountain plover (which prefers short grass–to–bare dirt) we are now detecting Grasshopper and Baird’s Sparrows (preferring taller, dense grass) where the prairie dogs have disappeared!

It’s important to document these kinds of changes over time so that we can learn about how external factors like climate, disease and land use affect the shortgrass ecosystem and its wildlife community. Different strategies can be implemented to achieve management goals, including enhancing habitat for certain birds and other animals. For example, prescribed burns create ideal conditions for Mountain Plover nesting habitat. Flea dusting and vaccinations helps protect prairie dog colonies from experiencing local extinction due to sylvatic plague, and rotational cattle grazing or fencing in temporary pastures can create patchy areas of grass heights that provide habitat for a variety of grassland birds and other wildlife.

Left: Baird’s sparrow on Meadow Springs Ranch, photo by Walter Wehtje Right: Burrowing owl, photo by Gerhart Assenmacher

The data Bird Conservancy of the Rockies has collected in the Mountains to Plains region over the last 11 years has allowed the City to respond to management challenges in real-time and take actions to restore declining populations. It’s a wonderful example of how collaboration and partnerships can positively affect conservation and land management for our sensitive grassland birds and their habitat. It’s also a great case study for the importance of long-term monitoring. We wouldn’t have learned what we have in a shorter time span. And, the effort is ongoing! This year, we continue to closely monitor the presence and possible nesting activity of Baird’s Sparrows at Soapstone, as well as what’s happening with other birds.

Soapstone Prairie and sky, photo by Erin Youngberg

We encourage you to see this special place for yourself! There are almost 18,000 acres open to the public in Soapstone Prairie Natural Area where you experience the beautiful shortgrass prairie and see flowers, birds, pronghorn, bison, prairie dogs, coyotes, badgers, foxes, and more!

Soapstone flowers (Top L-R) are Yellow aster, Scarlet Guara, Scarlet Globemallow. Click here to download seasonal wildflower identification guides created by Lynn Rubright, Fort Collins Natural Areas Master Naturalist. Photos bottom (L-R): Horned Lark nest w/ eggs, baby pronghorn. Photos by Erin Youngberg.

Visit Soapstone Prairie Natural Area

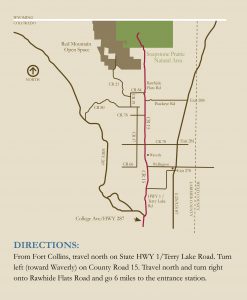

Soapstone Prairie Natural Area is a 28-square-mile (73 km) park and conservation area located in northeastern Larimer County, Colorado. The City of Fort Collins purchased the land for Soapstone Prairie Natural Area in 2004, which was opened to the public in 2009. The site features over fifty miles of hiking trails, interpretive exhibits, picnic facilities and terrific wildlife viewing opportunities. Hours vary seasonally. Before you visit, be sure to check the Fort Collins Natural Areas website for current conditions and to download a visitor brochure.