Using radio to study grassland bird movement

Grassland bird populations have declined by half over the past four decades. We attribute these declines to habitat loss and degradation related to cropland expansion, urban development, drought, shrub encroachment, and mismanaged grazing practices, however grassland birds remain mysterious and we lack the knowledge to effectively conserve them.

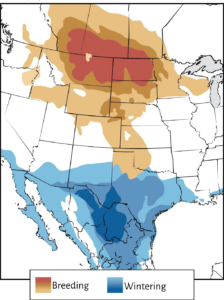

Many grassland birds of North America utilize the vast and remote Great Plains and Chihuahuan Desert (GPCD) region at some point throughout their annual cycle. This region stretches from Canada through the central United States into northern Mexico, and contains the majority of remaining grasslands in North America.

Across the Full Annual Cycle

Bird Conservancy of the Rockies and partners have been studying grassland bird survival and ecology during different parts of their full annual cycle with the goal of answering pressing questions that can help guide strategic conservation and management of grasslands in the GPCD.

One of the biggest knowledge gaps for imperiled species such as Baird’s Sparrow, Sprague’s Pipit, or Thick-billed Longspur exists during the nonbreeding season. We know almost nothing about migratory movements, routes, and stopover sites to rest, refuel and molt their feathers. Little is known about connectivity between the breeding and wintering grounds. Because these birds are small and live in remote regions, there are challenges to studying them during migration or over large distances.

Reading birds, loud and clear

Recent advances in tracking technology bring us closer to filling in knowledge gaps for grassland birds. Bird Conservancy is spearheading the development of a collaborative network of automated radio telemetry stations in the GPCD region as part of a world-wide network, the Motus Wildlife Tracking System. This exciting project combines technological advances with avian research and conservation efforts across the full annual cycle of grassland birds. Using data collected from Motus, we are sure to learn new things and fill in specific gaps in our knowledge of the ecology of and risks to these important birds.

Motus is an effective method to explore migratory bird movements and involves stations made up of antennas mounted to a structure and connected to a simple radio receiver. Birds, tagged with coded radio transmitters that pass within roughly 10-15 miles of a Motus receiver station, are logged by the receiver and then uploaded to an online database. The tags can last for months to several migratory seasons depending on their battery power, without needing to recapture the individual to retrieve data. The receiver stations are “open” to receiving data from birds tagged by any researcher so a single station can collect data from any number of species!

A network of listening posts

Managed by Birds Canada, Motus is currently made up of over 1000 stations operated by nearly 900 different organizations and researchers—and it continues to grow. To date, data collected using Motus has resulted in over 120 scientific publications that have expanded our understanding of animal movements, habitat requirements, and much more. By utilizing this technology and working closely with partners and collaborators across this trinational region, we aim to :

- Develop a strategic plan for station placement and install stations following this regional plan

- Tag breeding and wintering grassland birds with radio transmitters that communicate directly with receiver stations

- Collect data to fill in knowledge gaps for declining species including Baird’s Sparrow, Thick-billed Longspur, Chestnut-collared Longspur, Grasshopper Sparrow, Lark Bunting, Sprague’s Pipit and others.

In the summer of 2020, we kicked off our regional Motus network development with the installation of two Motus stations here in Colorado: one at Soapstone Prairie Natural Area, a property managed by the City of Fort Collins, and another station at Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge, just outside of Denver. These stations were strategically placed in order to detect grassland birds using these important areas, and were built and installed at these locations with the help of the strong partnerships with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and the City of Fort Collins Natural Areas that Bird Conservancy has been able to develop over the years. We were also contracted by another long-time partner, The Nature Conservancy, to install two more stations at an important shorebird stopover site in central Kansas, Cheyenne Bottoms Refuge, the largest inland marsh in the lower 48 states.

Last fall, Bird Conservancy organized two planning webinars (You can view them on YouTube: webinar 1 and webinar 2) connecting nearly 200 participants from Canada, the US, and Mexico to share goals and plans for the GPCD Motus network. Motus was new to some and this provided an opportunity to inform and advance conversations about collaboration. We learned where partners planned to install their own networks and what species and geographic areas were relevant to their research questions or conservation needs. Feedback from these meetings is informing Bird Conservancy’s Motus station site planning across the Great Plains and Chihuahuan Desert.

This year, we are planning to install stations across Kansas, Nebraska, and here in Colorado. If all goes as planned, we’ll have nearly 20 more stations installed as part of our network, connecting lines of stations in the Midwest all the way into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. With a number of university and nonprofit partners in Mexico and funding from the Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act, we have plans to install stations in northern Mexico to track birds once they arrive to the Chihuahuan Desert grasslands. Several partners within the GPCD geography have also installed stations or have funding and their own plans for Motus stations and grassland bird tagging in 2021.

Keep an eye out for upcoming posts as we get our station installation and bird tagging work underway in the coming months!

A small Motus station on top of a picnic shelter at the Kansas Wetlands Education Center at Cheyenne Bottoms Wildlife Area, in central Kansas.

MORE RESOURCES

Click here to download an information sheet about Bird Conservancy’s Motus initiative.

GPCD MOTUS Google Group – This Listserv is for sharing the latest updates on the GPCD Motus project, learning about Motus-related work happening in the region, and connecting with other researchers.

Partners in Flight (PIF) Motus Initiative – This project is a part of a larger effort to develop the Motus Wildlife Tracking System throughout the western United States. PIF organizes a monthly discussion with other researchers working on Motus in the West.