The Mountain Plover is a ground-nesting small-bodied shorebird endemic to the shortgrass prairie of the Great Plains—meaning it is only found there. Like many grassland birds the Mountain Plover population is on a steep decline at about 75% drop since the 1960’s. Mountain Plovers are well studied on their breeding grounds since they can be easily seen, if you know what to look for, and tend to stay close to their nest once established.

But what happens with these birds when they migrate for winter? That is the missing piece of the puzzle!

We still know very little about the details of birds’ lives during migration, which raises fascinating questions that are also important to conservation strategies.

Let’s take a step back and first think about migration. What is that?

Well, think about going on a car trip across country and along the way you need to stop and get gas or food. Animals do the same thing, including most birds as well as many mammals and insects. Migration is the seasonal movement of animals from one region to another (from summer to winter and vice versa). Instead of gas stations and grocery stores, however, birds need good habitat to stop at—called “stop-over sites”. They are spots that provide food, water, and places to rest and recharge before continuing on the journey. Their final destination may be hundreds (or in some cases, thousands!) of miles away. Many birds spend their winters further south where it’s warmer and food is more abundant. In order to effectively conserve birds, you really have to know about their full annual cycle: on the breeding grounds, during migration at stop-over sites, and on the wintering grounds.

How do we learn where plovers are going?

How do we learn where plovers are going?

We can learn a tremendous amount about migratory movement by banding birds. Banding was the first scientific method used to track migrating animals. Many millions of birds have been individually banded, providing important insights into bird migration timing, movement patterns, and locations visited. Most of what we know today about migratory routes, stop-over sites, and wintering areas can be attributed to the continuing work of regional and national bird banding programs. Plover species and other waterbirds in general are easily seen and good candidates for banding studies.

Mountain Plovers have been banded in various parts of their breeding range for more than 20 years in places like Montana, Colorado and Nebraska. We have already learned so much about these birds thanks to monitoring efforts. Since we now know that adults banded one year will return the next year to the same breeding site, we can keep an eye out for them. We can also use bands to determine whether juvenile plovers survive their first year by looking for them each subsequent season. For instance, a graduate student saw a banded Mountain Plover from 2005 in the same breeding area 10 years later.

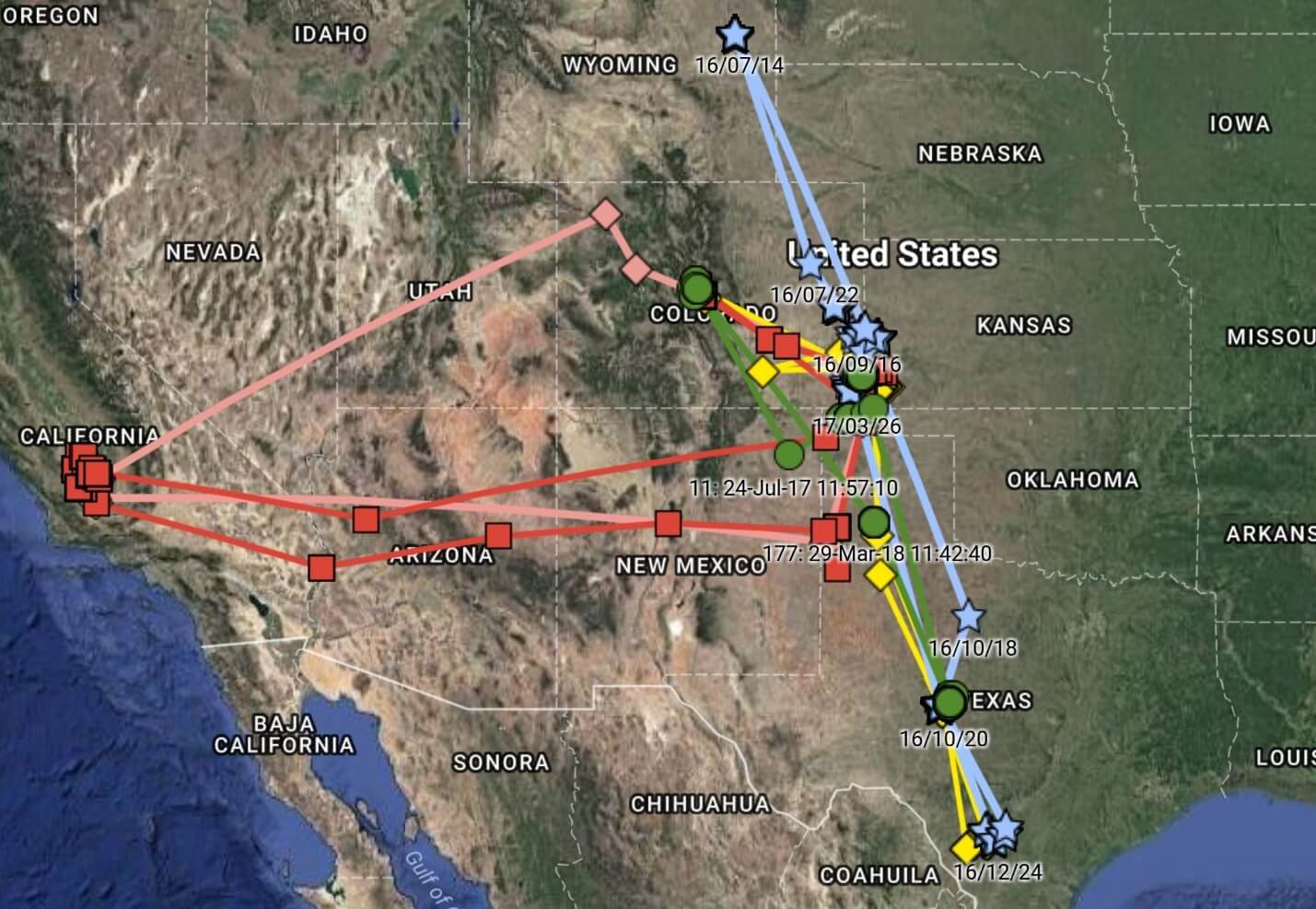

Banding is not always the most efficient way to answer specific questions about migration, so researchers are using technology to take the next step. The video and image below show how migratory route data from GPS tags provide details about plover travels. Each color represents an individual bird and its movement in one year: three birds bred in South Park Colorado and one at Thunder Basin National Grassland in Wyoming.

What’s next?

Lack of information about wintering areas limits conservation strategies. We need to understand challenges on migratory and wintering grounds. Bird Conservancy recently received a Neotropical Bird Migratory Conservation Act grant in 2018 to further study Mountain Plover migration and connectivity. This will expand upon what we have learned from the GPS tags. Bird Conservancy is working in collaboration with Mike Wunder Ph.D of University of Colorado-Denver, Steve Dinsmore Ph.D of Iowa State University and Pete Marra Ph.D of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. We are also engaging with new potential partners in key wintering areas such as Texas. We look forward to applying what we learn about Mountain Plovers to address these conservation challenges and identify potential solutions on migratory and wintering grounds.

Meanwhile, we are in the midst of fall migration so keep an eye out for banded birds of all kinds and banded plovers during migration and winter! They tend to form large flocks and can be easy to spot. We’ve seen many photos of banded plovers show up on e-bird postings. We also encourage you to submit your sighting info to the Bird Banding Lab as well. The data gathered by citizen scientists is invaluable in adding to our knowledge and understanding.

We have only begun to scratch the surface when it comes to understanding Mountain Plover. With each season we come closer—and ultimately saving this special species!

For more information about our Mountain Plover research and conservation work, contact Angela Dwyer.