Welcome to the final installment in our 4-part series (click here for the first entry) exploring perspectives on modern ranching.

Jessica Weathers (Private Lands Wildlife Biologist) spoke with Wyoming ranchers Marilyn Mackey and Tom Reed about family heritage, the influence of the oil and gas industry, changing conservation practices, and challenges facing the future of ranching in rural America. In today’s post, they share their perspectives about sustainable management approaches, and why they love what they do.

Days in the Lives of Ranchers (Part 4 of 4)

Sharing the land with native wildlife

Ranch owners Marilyn Mackey and Tom Reed—introduced in part 2 of this series—welcome many wildlife species to their land.

“Just about every kind of prairie animal,” says Marilyn happily. “Sage grouse, all the hawk species, on the western part of our place there are bluebirds; we have robins, sparrows, prairie dogs. We have coyotes, foxes, badgers, raccoons, deer, antelope, elk.” She says it’s still a thrill for her to see them on her property, “except when they get in my garden.”

Tom and his family are no newcomers to conservation topics. His ranch is certified as “bird friendly” by the National Audubon Society and is one of over 20 ranches participating in the Thunder Basin Conservation Strategy, coordinated by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Several members of his family helped launch the Thunder Basin Grasslands Prairie Ecosystem Association. When asked about wildlife on his property, Tom replies, “I certainly know a lot of them…but there’s a lot of the birds that I don’t know.” Several agencies and conservation groups regularly conduct bird and wildlife surveys on his property.

Maintaining healthy, sustainable grasslands

Both Tom and Marilyn have participated in conservation programs offered by Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) with the goal to improve their operations and better utilize their land. The end result is a productive landscape that also provides prime habitat for wildlife. Ranchers enter into these programs for multiple years and can continue to use these management techniques once the conservation agency’s involvement is finished. The greatest advantage of these programs for conservation efforts is to form lasting relationships with landowners, opening channels for two-way communication between researchers and ranchers.

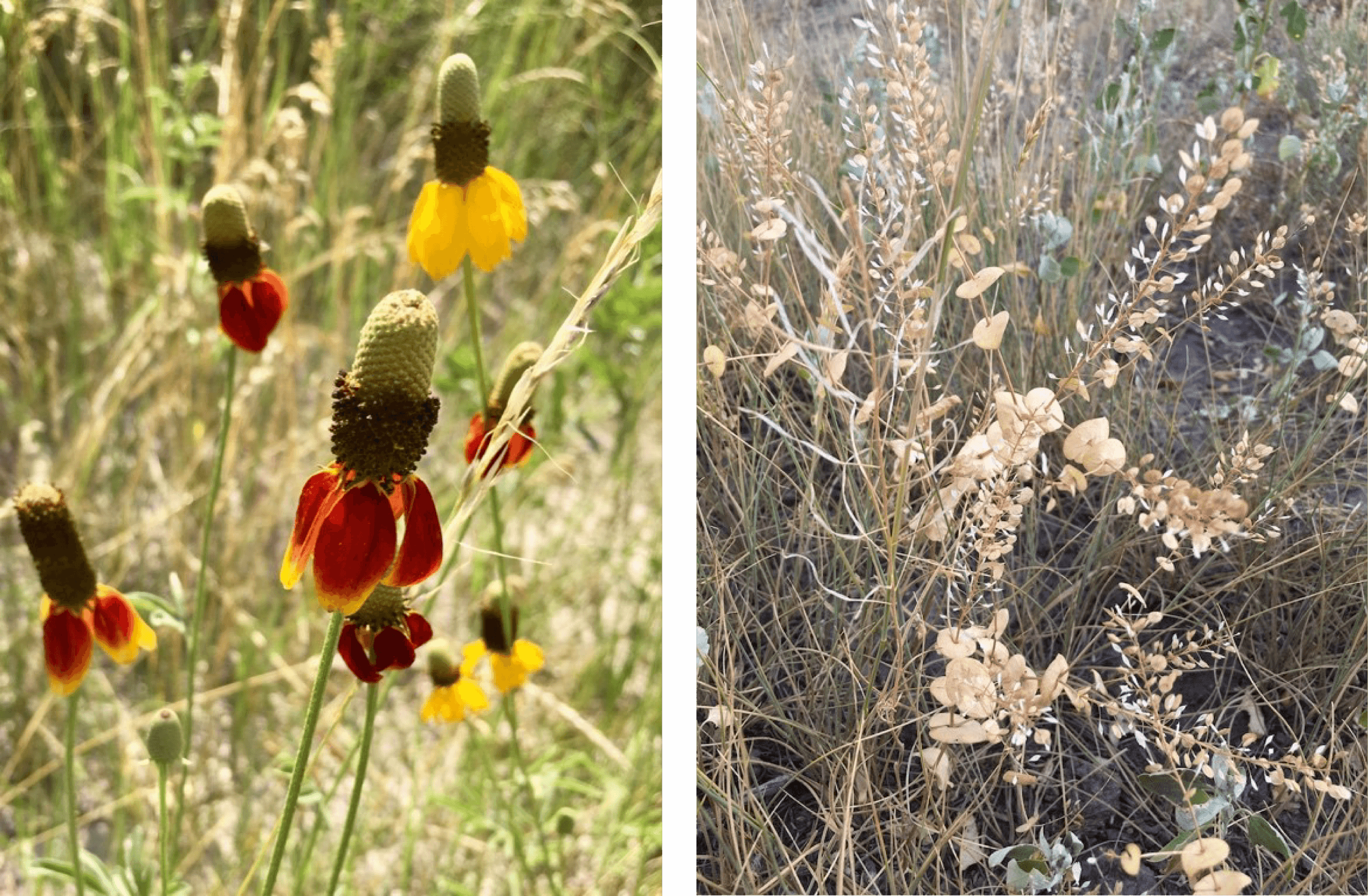

“From a management perspective, we are managing grass.” Marilyn says, “and if you don’t take care of it and you don’t manage it, then it’s not there. So we have to do the best job that we can.” This involves regenerative grazing practices and water management, which requires infrastructure like fencing and water retention/conservation methods. Natural (or human-caused) disasters such as fire can wreak havoc on carefully-laid plans. Sagebrush grows slowly, takes a long time to regenerate, and landowners are not compensated for sagebrush losses in the event of a fire. While not considered great forage for cattle, it provides other benefits such as protection for livestock from the elements, and water retention by capturing snowfall. The negative impacts of sagebrush loss on a landscape are long-lasting.

The fight against weeds

Tom listed off several projects he had done through conservation agencies. “We’ve drilled water wells, we’ve done dirt work, we’ve done grass monitoring, we’ve done nutrition balance. They all have their upsides. I have some cheatgrass and cactus spraying work that’s going to be done.”

Cheatgrass, also known as downy brome, is an invasive species that outcompetes native grasses, absorbing excessive amounts of nutrients and water from the soil. Prickly pear cactus, while native, can be problematic. As it spreads into degraded rangeland or bare ground, cattle graze areas without cactus more heavily. This creates more bare ground and perpetuates the cycle. Tom is fighting back with the help of conservation programs, using herbicides to control the spread of noxious weeds. In addition to fighting invasive species, Tom implemented a rest-rotation grazing system. He rotates his cattle from pasture to pasture in accordance with the growth stage of the forage. This practice is a vital part of sustainable rangeland management, stimulating vegetative regrowth and promoting soil health.

“Developing water resources is especially valuable.” ~ Tom Reed

Water is a huge resource concern shared among most producers in NE Wyoming. With very little precipitation on an average year—only 12-14 inches in most of northeast Wyoming—droughts can be devastating.

“I do a lot of rotation,” said Tom, whose pastures are subdivided with electric fencing to manage livestock in relation to water sources. His newest well will be strategically placed to provide water for four different pastures.

“One of the challenges we have always had on our ranch is watering the livestock and getting it where it’s dispersed, so they aren’t all just congregating in one area,” says Marilyn. Livestock can over-utilize grazing areas if water sources are not properly distributed, causing damage to the vegetation. Water infrastructure plays a role in the health of the land beyond just the needs of livestock. “Years ago, my granddad was involved with the Campbell County Conservation District,” says Marilyn. “He enrolled in programs where they install erosion control dams and terraces. We have some really steep country, so when it rains hard, there’s a lot of runoff and erosion is a problem. We still see the benefits of those installations.” Marilyn’s ranch also participated in a rotational grazing program with NRCS about 15 years ago, and continue to use that management technique today.

Love for the land and ranching

As we finished speaking, I asked Tom what advice he might give someone wanting to start ranching. He gave a wry smile, “Marry into it?” His answer had a sad undertone of truth. He continued, “It would be hard to start now. The cost of land is so high that you almost have to have an outside job to support it. And, if you have to have an outside job, unless you really, really want to ranch, why would you ranch? To me, it just wouldn’t be worth it. You’d have to born into ranching or marry into it. I was very lucky that my wife liked to ranch too.”

“If you want to know about ranching, go to the real ranchers,” advised Marilyn. “Don’t just look at pictures magazines. Don’t just read articles. Don’t believe what you see on TV is real. Because I’ve seen a lot of high-end magazines—even some ag magazines—where the picture they portray of ranchers is not really the people. They are not the “me’s” of this world. They’re not the people that we know, that are really out there working the land. You’re more likely seeing ‘hobby’ ranchers or people with a lot of money that have bought a big place. That’s also created a perception that all ranchers are rich, which isn’t accurate. So, I would just say, come out and visit us. We’ll take you for a real tour.”

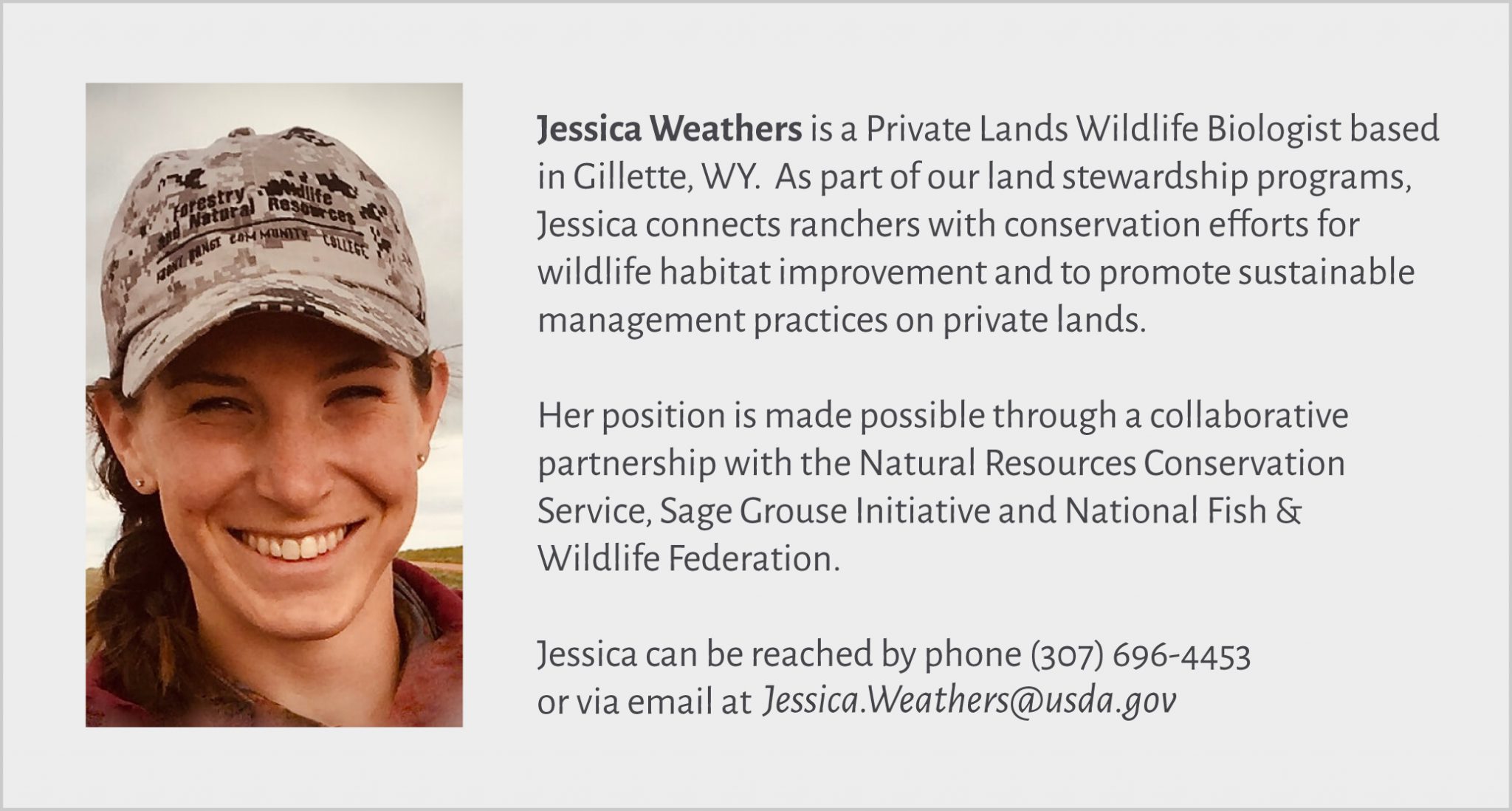

Jessica Weathers is a former Bird Conservancy of the Rockies Private Lands Wildlife Biologist based in Gillette, WY. This position was made possible with funding support from NRCS and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

Bird Conservancy of the Rockies works with private landowners, land managers and resource specialists to implement habitat enhancement projects. Our biologists and rangeland ecologists identify wildlife-habitat potential and help modify or develop on-the-ground practices that maintain or increase agricultural production and benefit wildlife habitat. For more information, visit our Stewardship page!