A banded Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus) is ready for release.

Photo credit: Seth Gallagher

Every October, thousands of tiny Northern Saw-whet Owls (hereafter, ‘Saw-whets’) quietly scatter across North America to their wintering areas. These owls were once thought to be uncommon—even rare. They are actually widespread, but fly ‘under the radar’ due to their tiny size, nocturnal habits and tendency to roam. For several decades, an army of owl-banders has been gathering data about Saw-whets along the largely forested East Coast of North America. However, less is known about how and where these owls move across the middle and western parts of the continent. Their migrations often cover vast distances with little forest cover, and there are many unanswered questions about their habitat needs, interactions with other species, and total population and distribution.

Project Owlnet is a network of migrant owl banding stations that was established to take a closer look at the life cycle and migratory patterns of Saw-whets. For the past eight years, Bird Conservancy has operated several owl-banding stations in the western Dakotas that contribute data to Project Owlnet. Theodore Roosevelt National Park in North Dakota, and Slim Buttes (Custer National Forest) and two stations in Black Hills National Forest in South Dakota are the first owl-banding stations to be established in the U.S. portion of the Northern Great Plains.

To catch an owl, we put an audiolure (Foxpro Game Caller, center) in dense vegetation and surround it with mist nets. After dark, the audiolure broadcasts the territorial call of a Saw-whet, attracting owls that are flying over or in the area. Photo credit: Nancy Drilling

Why study Northern Saw-whet Owls?

These owls are incredibly cute, which is probably enough to make some people want to study and conserve them. But they are also an important part of conifer forest ecosystems, which are facing multiple threats across North America. Examples include massive stand-replacing fires, large scale tree die-offs from insect outbreaks, urbanization, fragmentation and effects of climate change. Understanding how Saw-whets and other forest inhabitants are impacted sheds light on larger land management planning and needs.

Emily Nelson is one of hundreds of interns, volunteers, and visitors that have experienced the thrill of seeing a Northern Saw-whet Owl up close at one of our banding stations. Photo credit: Dan Svingen

Eight years of owls!

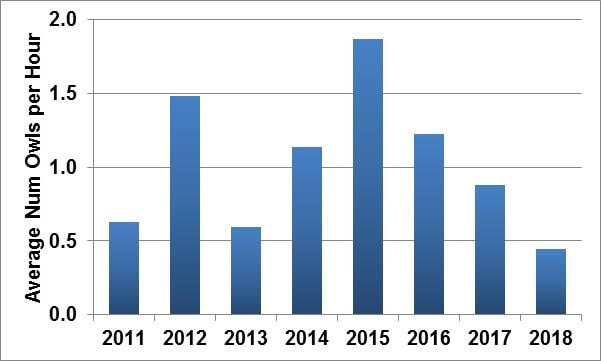

The 2018 fall owl-banding season was our eighth season. What have we learned? First, we have discovered that a lot of owls move through the western Dakotas during October! We have caught 1,355 Saw-whets, 16 Eastern Screech-owls and 29 Long-eared Owls. But, not every year is the same. The following graph shows that 2015 was a crazy busy year while this year was the slowest on record.

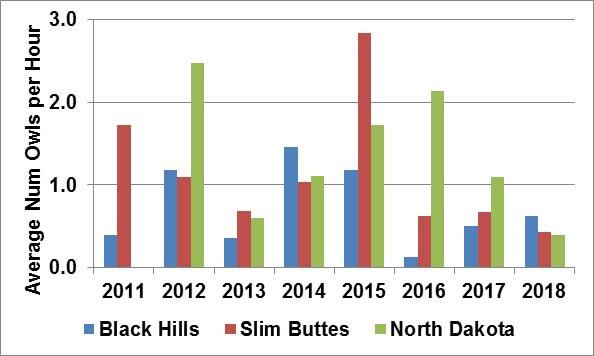

In addition, each banding station is different.

For example, in 2012 and 2016 Theodore Roosevelt National Park was the place to be while in 2011 and 2015, Slim Buttes was the hot spot. Variability in numbers among years and sites is typical for this species, prompting some biologists to describe Saw-whets as ‘nomadic’ rather than ‘migratory.’ There is a peak in numbers every four years , but each station’s peak occurs in a different year. This is a very intriguing result. We know that peaks are caused by exceptional breeding success the previous summer. The western Dakotas banding stations are relatively close together so we would expect most of the owls would be from the same source population. But our results suggest that the owls moving through each of our banding stations are coming from different locations that had different years of peak breeding. The story is complicated by the fact that Saw-whets breed in western South Dakota and the Nebraska Panhandle, but not in western North Dakota. If we can identify where saw-whets are occurring, we can better identify the threats that this species may be facing.

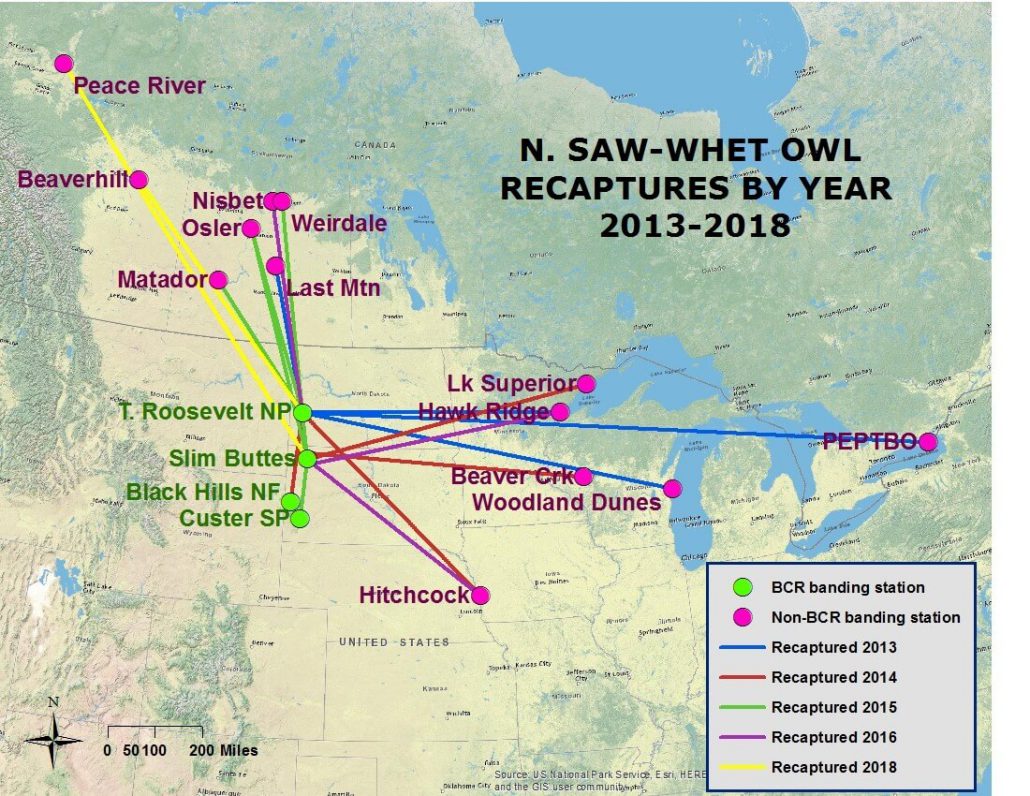

The most exciting part of banding is recapturing an owl that is already banded. At Bird Conservancy owl banding stations, we have had 28 ‘exchanges’ between banding stations, meaning that either we have recaptured someone else’s banded owl (12 birds), someone else has recaptured our banded owl (7 birds), or we have recaptured our own owl at a different station than where it was banded (9 birds). Here is a summary map of these recaptures (note that the straight lines should not be construed as the actual flight path of the owl).

Notable findings:

- We have exchanged owls with every fall owl-banding station in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Iowa! In fact, multiple owls have been captured between Bird Conservancy stations and Nisbet (3 owls), Osler (2 owls), Beaverhill Bird Observatory (2 owls), Hawk Ridge (2 owls) and Hitchcock Nature Center (2 owls).

- All but one of the ‘foreign’ recaptures (either banded or recaptured by a non-Bird Conservancy banding station) were in conjunction with Bird Conservancy’s Theodore Roosevelt station.

- The year matters. We had 9 recaptures in 2013, mostly of owls originally banded to the north and east. This year, we had two exchanges, both with banding stations to the northwest.

A word of caution about interpreting the map. There were no owl banding stations to the west or south of the Bird Conservancy’s stations for most of this time period. This means that our owls could be coming or going from those directions but we have no way of knowing. In the past three years, new banding stations have popped up in central Wyoming and the eastern Dakotas, giving hope that in the future we can fill in more of this map.

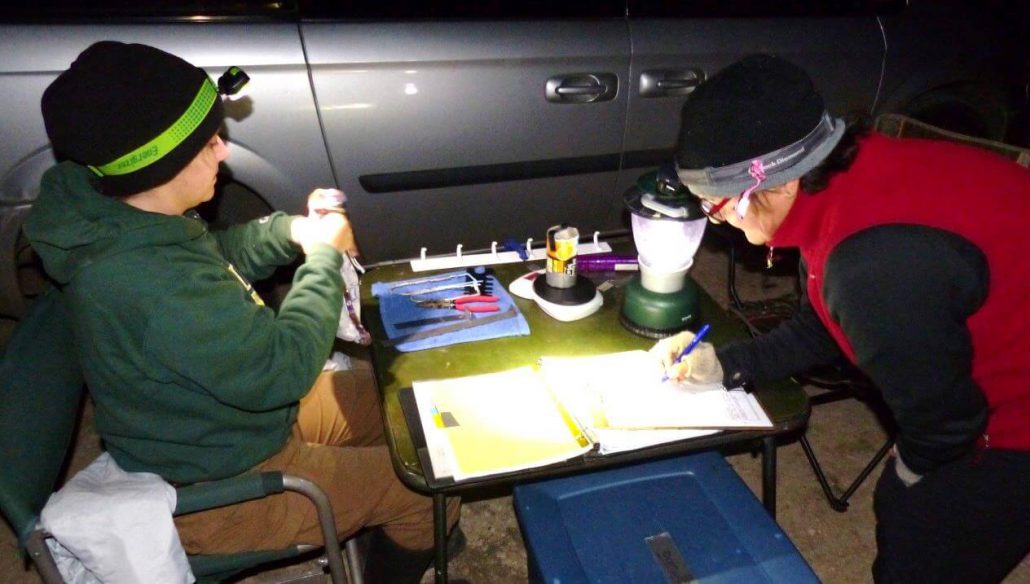

Intern Megan Massa (left) and bander Dawn Garcia (right) process a Northern Saw-whet Owl at Bird Conservancy’s Theodore Roosevelt National Park banding station. Photo credit: Peder Stenslie

So after eight years, we have begun to reveal some of the mid-continent movements of this charismatic, enigmatic little owl. But as often occurs in scientific inquiries, every discovery raises new questions! Where are the unbanded owls (98% of our captures) from? Why don’t we get more foreign recaptures at our South Dakota stations? Do our stations really have different four-year cycles and thus different source populations? And so on.

We plan to back at it next October. Come join us! Visit our Bird Banding page for more information about station locations, visiting hours and dates of operation.

For more information, contact: Nancy Drilling, Dakotas Projects Coordinator, via e-mail or by phone: (605) 791-0459