Trees and all vegetation are vital for animal life. Many parts of the world are rich in abundance of trees like tropical rain forests. However, should trees be planted everywhere? We hear “plant a tree, save the planet” but do we hear “cut a tree and save the grasslands”? Almost never and honestly what does that even mean?

Well to begin, approximately 25% of the Earth is a grassland biome. A biome is a large naturally occurring community of flora and fauna occupying a major habitat. Worldwide there are hundreds of animals that live in the grassland biome. There are over 300 species of birds that either permanently live in grasslands or that migrate in and out, and hundreds of different types of plants that contribute to diverse healthy grasslands. The Great Plains of North America is a vast rich landscape full of biodiversity and home to Indigenous Nations, farmers, ranchers and many others who depend on this landscape for their livelihoods. However, much of the Great Plains has been transformed since the 1800’s which included planting many, many trees.

Grasslands are rich in biodiversity. Some studies have higher biodiversity in grasslands and savannas than rainforests1. Photo by Angela Dwyer

In my process to think about how to frame this story, I did a little research. I was surprised at what I had learned…

The Prairie States Forestry Project, also known as the “Great Wall of Trees,” crossed 33,000 farms in six Great Plains states. Championed by President Franklin Roosevelt, it is recognized as one of the most ambitious forestation efforts in U.S. history. Although, many of the 1930s- and ’40s-era “shelterbelts” are now gone, many more have been replanted. Three years into his presidency and five years into the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt asked destitute Great Plains farmers to stop growing wheat and start growing trees. The idea seemed crazy. Unemployment was rampant in the mid-1930s, and families across the country needed grains for food. But Roosevelt said the federal government would pay farmers to grow trees in soils stripped by the Dust Bowl. Not just a few trees, but 220 million trees. This made sense at the time. Nearly 90 years later, the Great Wall of Trees remains one of the most ambitious federally funded, landscape-scale adaptation projects in history.

When trees are planted in a grassland it can get converted to a woodland and we risk losing an entire ecosystem. Eastern red cedars invading in western Nebraska. Photo by Angela Dwyer.

In my musings to learn more, I recently read a blog from Chris Helzer of The Nature Conservancy in Nebraska called The Prairie Ecologist offering the perspective of how Arbor Day originated. The founder of Arbor Day, Sterling Morton was not a fan of treeless prairies.

“So, these treeless plains, stretching from Lake Michigan to the Rocky Mountains, were unfolded to the vision of the pioneer as a great lesson to teach him, by contrast with the grand forests whence he had just emerged, the indispensability of woodlands and their economical use. Almost rainless, only habitable by bringing forest products from other lands, these prairies, by object teaching, inculcated tree planting as a necessity and the conservation of the few fire-scarred forests along their streams as an individual and public duty. Hence out of our physical environments have grown this anniversary and the intelligent zeal of Nebraskans in establishing woodlands where they found only the monotony of plain, until to-day this State stands foremost in practical forestry among all the members of the American Union.” -Sterling Morton, founder of Arbor Day in Nebraska.

Sadly, the Sandhills of Nebraska were once called a “wasteland” when in fact this vast expanse of some of the last remaining intact grassland is vital for many grassland critters (including humans) and is slowly transitioning to a woodland. The most famous example is the Halsey National Forest. The largest hand-planted forest (90,000 acres or 140 sq miles) in the world was planted nearly Halsey, Nebraska.

Five men planting trees in the 1800’s in Nebraska. Photo courtesy of Richard Gilbert.

How big of a problem is it?

There is no doubt that trees are wonderful, needed and some would see them as never a problem, but when you live in a landscape that is slowly changing before your eyes you begin to recognize this biome is collapsing.

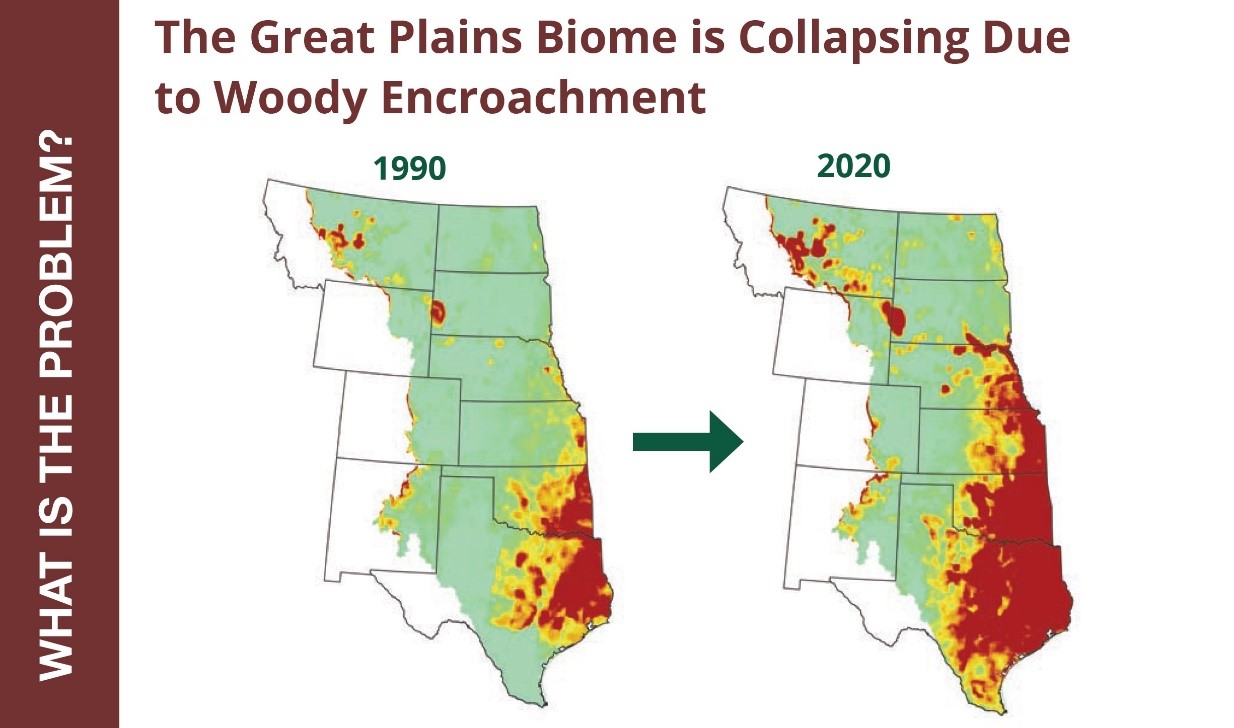

Red and yellow coloration on the map are trees (mostly eastern red cedar/mesquite) spreading into the great plains over time. See this factsheet for more information; Rangeland production losses to woody encroachment in the Great Plains. Dr. Dirac Twidwell from the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, used the USDA-Working Lands for Wildlife Yield Gap tool to estimate losses in terms of round hay bales. In 2019 alone, western states lost over 37 million round bales (1200 lbs each) worth of forage for livestock. Nebraska alone lost 698,880 bales, which can feed up to 88,466 cows.2 Livestock such as cattle are critical to maintaining healthy grasslands. Ranching can help achieve ecosystem benefits.

Red and yellow coloration on the map are trees (mostly eastern red cedar/mesquite) spreading into the great plains over time. See this factsheet for more information; Rangeland production losses to woody encroachment in the Great Plains. Dr. Dirac Twidwell from the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, used the USDA-Working Lands for Wildlife Yield Gap tool to estimate losses in terms of round hay bales. In 2019 alone, western states lost over 37 million round bales (1200 lbs each) worth of forage for livestock. Nebraska alone lost 698,880 bales, which can feed up to 88,466 cows.2 Livestock such as cattle are critical to maintaining healthy grasslands. Ranching can help achieve ecosystem benefits.

The collapse of this biome due to woody encroachment will negatively impact all the following: grassland bird abundance, wildfire risk, streamflow and water allocation, livestock production, herbaceous plant composition, insects, small mammals and even public-school funding. Research on all these and other impacts can be found here in the Eastern Redcedar Science Literacy Project.

- Thick-billed Longspur. Photo by Colin Woolley

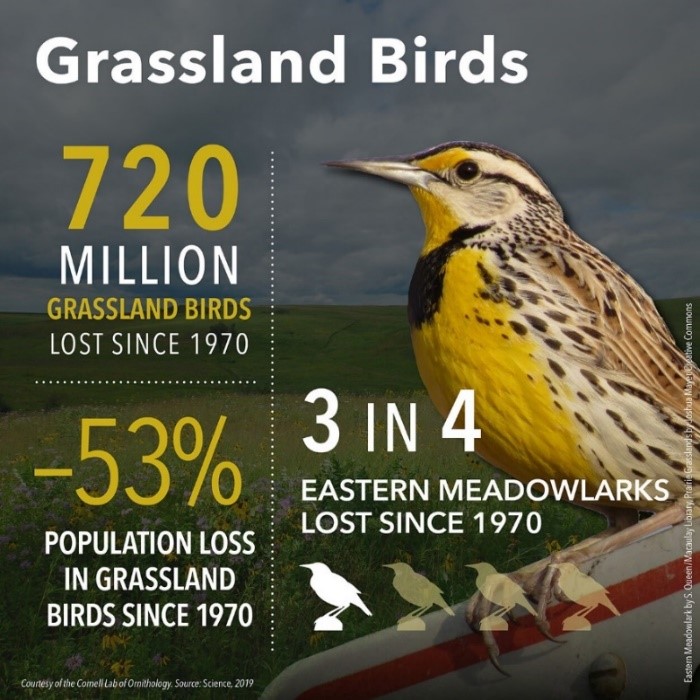

Published in Science in 2019, the findings show that 2.9 billion breeding adult birds have been lost since 1970, including birds in every ecosystem. Grassland birds are the guild in the steepest decline. Loss of habitat is the driving factor which includes conversion from a grassland to a woodland. Thick-billed Longspur (photographed above) is a grassland bird endemic (unique) to the Great Plains, and need shortgrass prairie habitat and little to no trees in the prairie. They are among the species in the steepest decline.

The benefits that grasslands provide are numerous. Grassland conservation will only be successful if people see grasslands as valuable. To many, these open expanses of prairies often seem empty, in part because the elements of nature most people are drawn to such as mountains and trees are missing in the prairie.

In 2022, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology teamed up with the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to produce a series of short films highlighting key aspects of the West. This one called Reconsidering Cedar focuses on the loss of grasslands in the Nebraska Sandhills, one of the most intact expanses of grasslands and potentially most at risk to conversion to a woodland ecosystem.

Private Lands Wildlife Biologist, Jackson Ebbers, in a woodland. A grassland that has been converted to a woodland state due to eastern red cedar encroachment in the Loess Canyons in Nebraska. Photo by Angela Dwyer

The challenge is working with landowners who have very few and younger trees, to engage with them to be proactive in removing younger trees, which is far less expensive. “I hear a common response from people that they don’t think woody encroachment can affect them for various reasons including soil type or lower rainfall. The eastern sandhills of Nebraska is one of the best examples to point to, to show people that woody encroachment can and will happen anywhere, and that soil type and climate are not barriers to spread.” -Jackson Ebbers

Everything is relative. I take what I hear and observe with a grain of salt and take it upon myself to research and review multiple perspectives. I once had no idea the trees I observed as I drove across the prairie might have a more negative impact than a positive one. When the right trees are planted in the right places, everything’s great.

Angela Dwyer is the Program Manager for the Northern Great Plains. Follow this LINK to learn more about our stewardship team and how to get involved. Grassland ecosystems have many benefits. Help spread the word! Download posters in English and Spanish here; Grasslands and You.

Angela Dwyer is the Program Manager for the Northern Great Plains. Follow this LINK to learn more about our stewardship team and how to get involved. Grassland ecosystems have many benefits. Help spread the word! Download posters in English and Spanish here; Grasslands and You.

Citations:

1Murphy, B. P., Andersen, A. N., & Parr, C. L. (2016). The underestimated biodiversity of tropical grassy biomes. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B, 371(1703), 20150319. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0319

2Fogarty, Dillion., C. Baldwin, P. Bauman, J. Beaver, R. Bruegger, D. Cram, L. Goodman, T. Hovick, A. Overlin, J. Scasta, C. Spackman, A. Thompson, M. Treadwell, D. Twidwell. Rangeland Production Lost to Woody Encroachment in Great Plains Grasslands. https://agrilife.org/westtexasrangelands/files/2023/07/GPGEP_UNL_01_Production-Losses.pdf. 2023.