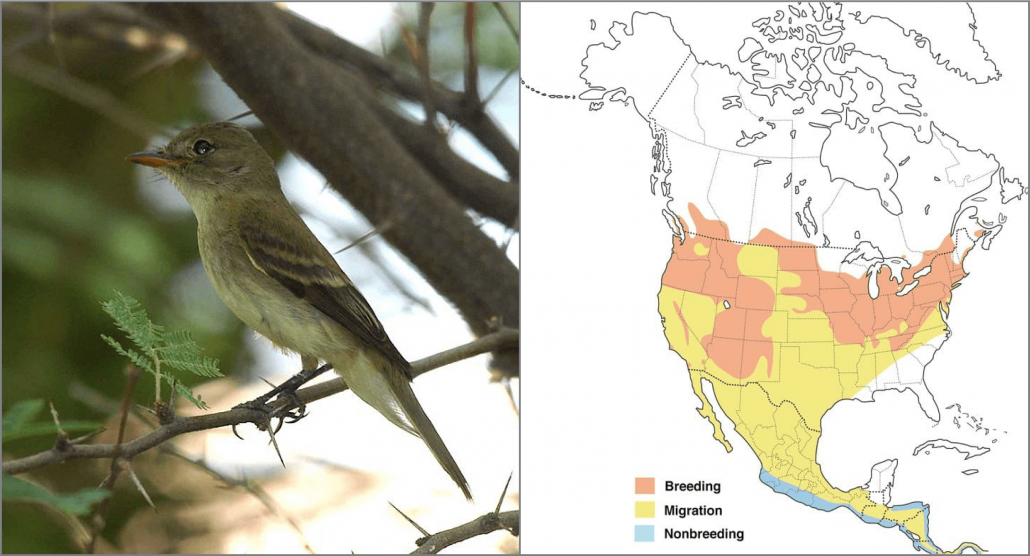

Southwestern Willow Flycatcher, Photo: USFWS Pacific Southwest Region. Migration map by Cornell Lab’s “All About Birds“.

Each summer, Southwestern Willow Flycatchers fly over 1000 miles to the San Luis Valley to enjoy the abundance of the Rio Grande with the hopes of finding summer love. While this journey is quite an impressive feat for a six-inch bird, migration is a common phenomenon for many avian species that we enjoy in the United States and spring marks the return of hundreds of species of migrants to our backyards.

Migration Miracles

There are a wide variety of migratory behaviors across avian species. While some birds migrate from high to low elevations, others migrate long distances, crossing multiple states or even spanning continents. Many factors signal birds when it is time to migrate, including seasonal temperatures, resource availability, and genetic disposition. These timing mechanisms are very delicate, and migration can be a particularly vulnerable period for birds because of the considerable time and energy it takes to travel long distances, and exposure to predators and unfamiliar stopover points along the way.

Our wetlands, forests, grasslands, and coastlines are home and haven for both resident birds and migrators. Each of these habitats has its own vulnerabilities. Scientific research and the natural disasters we see in our news broadcasts vividly demonstrate how our forests have become increasingly vulnerable to climate change through the impacts of fire and extreme weather events.

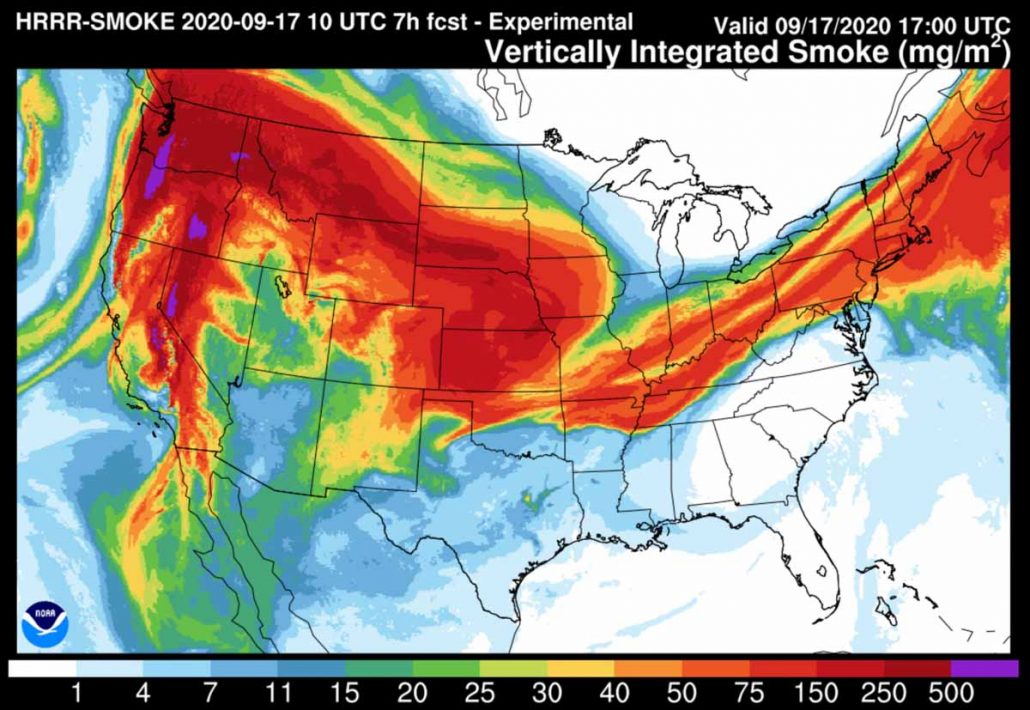

NOAA forecast map for vertically integrated smoke, which includes smoke high in Earth’s atmosphere that can produce red sunrises and sunsets. Sept. 17, 2020

Late summer’s wildfires in California shrouded the Bay area in a smoky orange haze. Photo: Michael Sturtevant

Complex Consequences

Summer 2020 saw devastating wildfires across many western U.S. states. Dense, noxious smoke produced by the fires blanketed the landscape. There is evidence to suggest that these wildfires, combined with unusual weather events, impacted birds far beyond normal seasonal variations. The worst occurred at the height of migration when the birds were already particularly vulnerable. In September, thousands of birds were documented to be ‘falling out of the skies’ dead across the Southwest.

Like a double-punch, fires and weather can have far-reaching implications that affect huge areas and many habitat types. In Colorado, late summer’s unprecedented forest fires had already put migratory birds at risk for starvation and smoke inhalation. September then brought record-breaking cold and heavy snowfalls that downed trees. Limbs full of foliage, seeds and fruits tumbled to the ground, reducing shelter and food sources. Insects, which many birds rely upon, were suddenly gone. Scientists are still working to understand the role that fire and weather played in the mass die-off, but early analysis indicates that starvation was a factor.

Colorado saw a record-breaking snowfall in Alamosa, CO in September, accompanied by 60-70 degree temperature swings. Photo: Emily Chavez

This Red-breasted Nuthatch was found dead in the San Luis Valley following the snowstorm. Photo: Emily Chavez

We see similar extremes on our coastlines and maritime areas, which also provide critical habitat for many bird species. In the Southeastern U.S., NOAA predicted that this year would be the most active hurricane season in its 22-year monitoring period. Coastlines shift, habitat characteristics change, and nests are destroyed by the high-speed winds of increasingly intense and frequent hurricanes. The cumulative effect leaves birds with specific habitat requirements struggling to survive. Even adaptable species struggle to forage and nest under such challenging conditions.

Focusing on Solutions

Big issues like these call for immediate and meaningful solutions. We need to learn more about the full annual-cycle of migratory birds and identify the biggest challenges to their survival. We need to minimize the impacts of extreme weather on wildlife by increasing the resiliency of diverse habitats, including working landscapes, and adapting management approaches to meet changing conditions. We need to inspire people of all ages toward an appreciation for the natural world and being good stewards of the land for future generations. Everyone can help soften our footprint and aid birds, from making our backyards and communities more bird-friendly, to encouraging consumption of bird-friendly products.

Visitors learn about bird banding during a visit to the Barr Lake Banding Station, 2018.

Fighting for the Future

Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, and many of our partners, do this work. Our researchers perform large scale monitoring of bird species, and deploying technological tools, like the MOTUS network, to learn more about bird migration. Bird banding contributes to our understanding of migratory routes and timings, species’ range limits, average lifespans, and how all these life-history characteristics may be changing over time. This data also informs our understanding of the potential impacts of extreme weather and fire events brought about as a result of a changing climate.

Our private lands wildlife biologists help manage for fire resilient forests and drought-resistant grasslands, healthy riparian buffers and building robust wetland ecosystems by working with landowners to improve management practices on their property. Our educators provide learning opportunities to develop a deeper awareness, enjoyment, and appreciation for the natural world.

All of this is part of our coordinated effort to increase and maintain healthy refuges for birds across their full life cycle. For vulnerable species like the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher, building habitat resilience is critical in the face of a changing climate and the challenges it brings.

Willow Flycatcher. Photo: Dave Menke, USFWS.

Emily Chavez is based in Alamosa, CO and employed by Bird Conservancy of the Rockies with funding support from Natural Resource Conservation Service, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Intermountain West Joint Venture and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Further reading/resources on this topic:

Click here to view the full article online.

What’s going on with all the dead birds across Colorado and the Southwest?

September 24, 2020| The Denver Post | September 24, 2020