After another winter of fieldwork down, we have managed to gain even further insights into the winter ecology of Baird’s and Grasshopper Sparrows. This season’s strong El Niño presented enormous challenges for these birds. Imagine a small sparrow, dripping wet in near freezing temperatures, huddled in a patch of equally damp grass. In order to survive such damp and cold conditions, sparrows need to find and eat enough seeds, an activity which takes them out in the open and in clear view of predators. This predicament, combined with a high number of predators around, may explain the high levels of mortality that we observed this season.

Although studying how and why birds die can be disheartening, this data will be critical to the conservation of grassland birds. And that is why we do it!

- A Grasshopper Sparrow captured in Chihuahua Mexico is ready to be tracked following deployment of a tiny radio-transmitter. This winter we recaptured two sparrows that were tagged in prior years. One individual has been captured in the same spot the last three winters! Photo by Erin Strasser

- Those neon Frisbees aren’t just for fun. A toss of the Frisbee as a bird is about to fly above or around the net has increased our capture and recapture rates. Recapturing tagged birds is just as important as capturing and deploying transmitters. Our goal is to remove transmitters so that birds have an increased chance of surviving the tough migration between the Chihuahuan Desert and the Northern Great Plains. Photo by Alejandro Alvarez

- Chuy Ordaz, a biologist from Ciudad Juarez, has been involved in the project for 3 years. Here he is extracting a bird captured in a mist net. Photo by Alejandro Alvarez

- Mexican biologists and local university students gain hands-on field experience through working and volunteering with Bird Conservancy of the Rockies. By participating in bird banding and radio-telemetry activities they gain valuable skills in the field of wildlife biology. Photo by Alejandro Alvarez

- When birds go missing, it’s time to pull out the big antennas. The “busca aves” (bird searcher) is a large antenna mounted on a pole that detects radio tagged birds that have moved beyond the study area. Photo by Erin Strasser

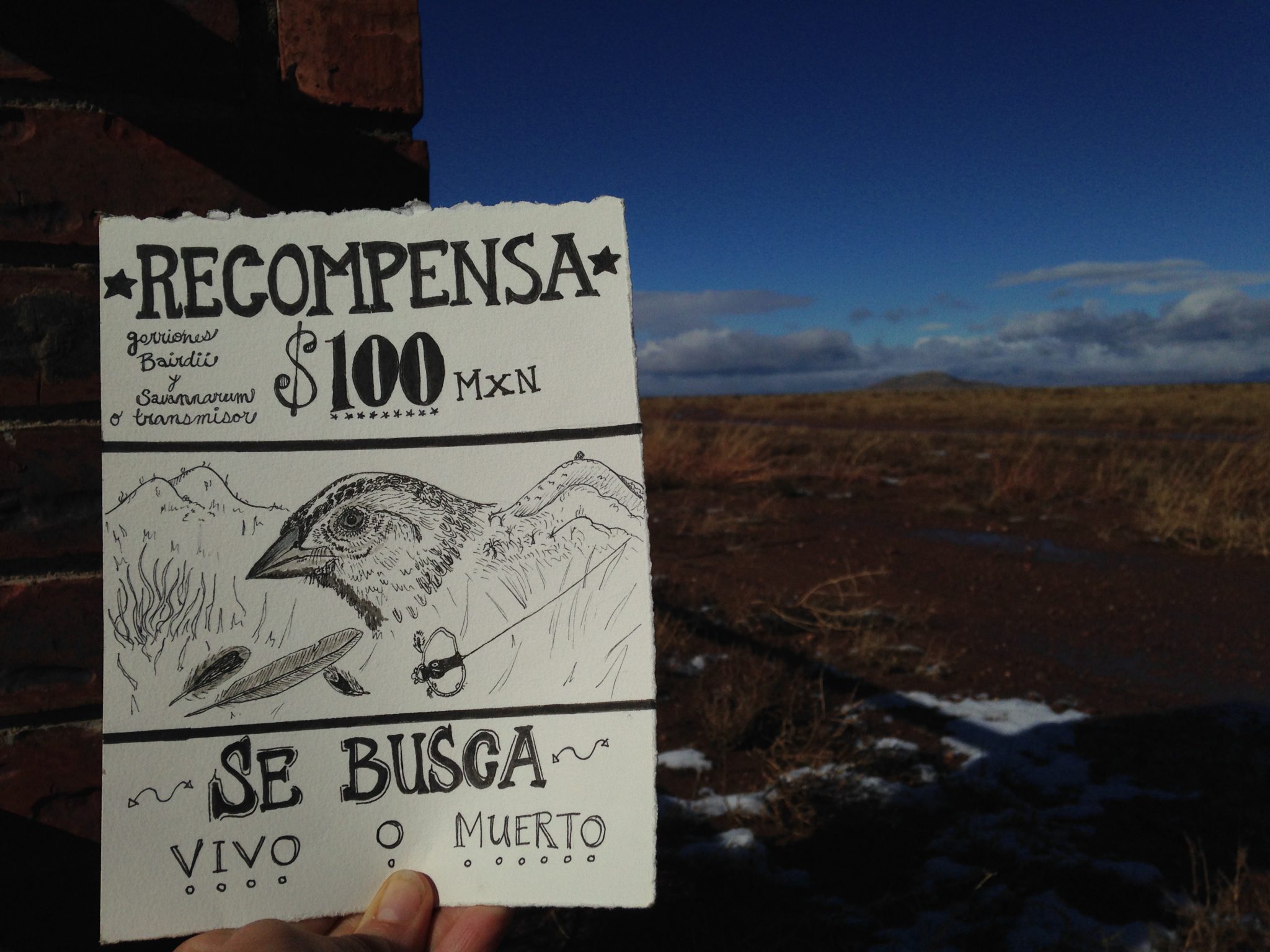

- Baird’s and Grasshopper Sparrows like to move—a lot! Age, sex, grassland conditions, bird densities and other factors may contribute to this behavior. All of this movement means that many birds go missing. In order to estimate survival rates we must find these birds, and a little monetary motivation never hurts! Photo by Erin Strasser

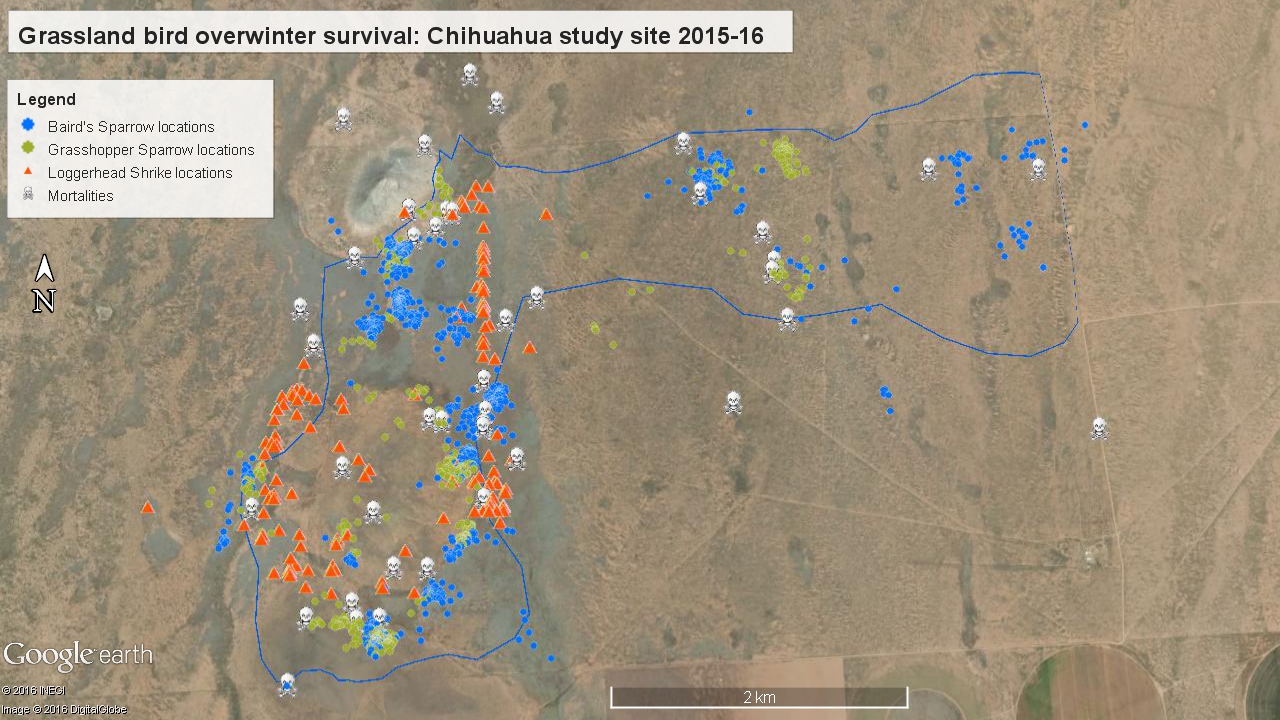

- We tagged and radio-tracked six Loggerhead Shrikes to gain insight into their movements and effect on sparrow mortality. The shrikes hang out along the edges of sparrow habitat on tall perches like shrubs and fences. This map of shrike locations (red triangles) in relation to sparrow locations (blue and green dots) suggests that the shrikes have created a virtual barricade. When a sparrow moves outside of its territory, shrikes have a good chance of capturing them as they pass through.

- Longtime partners from UANL and UJED are collecting data at sites in the Mexican States of Durango and Coahuila to give us a broader perspective on survival rates. Grasslands with taller shrubs and the predators that use them pose a challenge to grassland obligate species like Baird’s and Grasshopper Sparrows. The Durango site (pictured) has had very high mortality rate, likely due to the tall shrubs. However, it is important to note that many of the predators of our sparrows, (Loggerhead Shrikes, American Kestrels, Northern Harriers) are declining species as well. Photo by Erin Strasser

- Coolest bird capture of the season: The “correcamino”, or Greater Roadrunner, which could easily be mistaken for a dinosaur! Photo by Erin Strasser

- Badger, Bird Conservancy’s most enthusiastic sparrow herder, takes up the rear as the crew finishes up a productive day of recaptures. It takes enormous effort to capture and recapture the sparrows and we are lucky to have such dedicated volunteers. Photo by Erin Strasser

Thanks to our partners and funders: Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Juárez del Estado de Durango, USFWS Neotropical Migratory Bird Act, The US Forest Service International Program, The WWF Carlos Slim Foundation and the Canadian Wildlife Service.